|

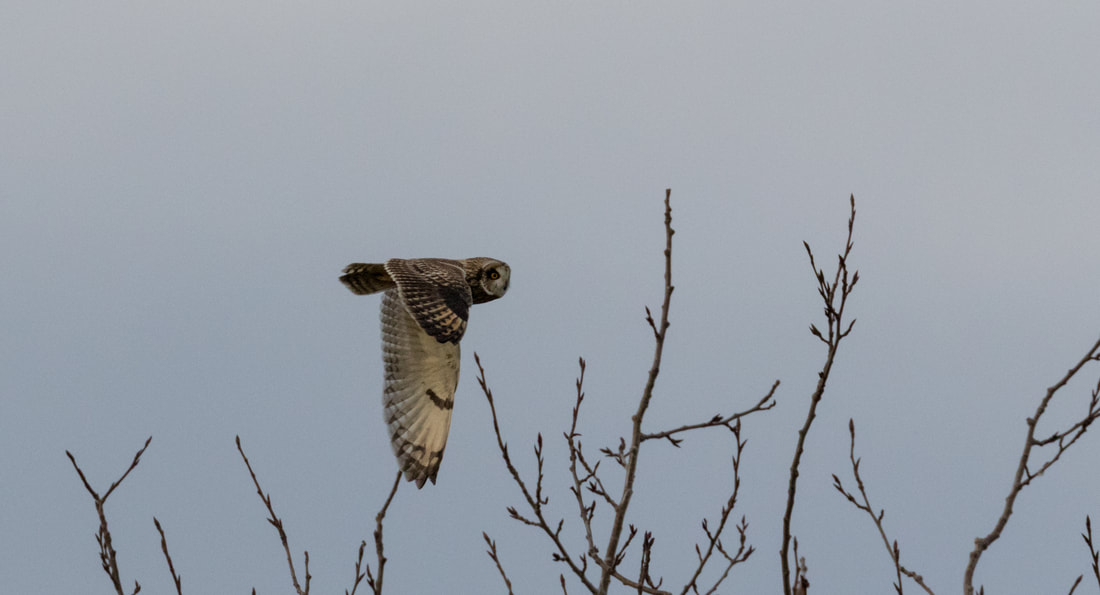

I woke well before dawn, my brain coming online in a flash of realization that today would be our final day of travel. Tara and I had a quick breakfast with our wonderful hosts, Fred and Fran, grabbed some extra coffee for the road, and were on our way. We made a quick stop at Trader Joe’s for some supplies (e.g. copious amounts of cheese for Tara) and then continued north towards what we thought would be smooth sailings across the border. We were mistaken. As we approached the border crossing, there were two booths open; one had a slightly shorter line, so naturally I opted for that one. In what must be a universal law of waiting or traffic lines, the one I selected immediately stopped moving. Three cars passed through the other gate before our first car was allowed to proceed. I probably should have realized then that things were not going to unfold the way I had envisioned. When we finally made it to the booth, the agent at the gate was quite friendly, and chatted with us about a rescue bulldog we should keep an eye out for when we got to Ladysmith, and the best cinnamon rolls in town (Old Town Bakery). Almost as an afterthought, he mentioned that we would need to go inside to talk with one of the customs agents because of the proposed length of our stay (5-6 months). We pulled over, and went inside, where we were subsequently interrogated for 30+ minutes by a dour young customs agent sporting an unusual hairdo; that is, he had very little, and what he had was gelled into little spiky islands. I’m not sure if there was a deeper meaning in his hair with respect to the current global trend towards greater insularization, but it was clear from the outset that he took his job very seriously. It also became clear that he considered two biologists with Ph.D.s looking to spend 5 months in his country writing papers and grants, highly suspicious. He wanted us to convince him that we would not seek illegal employment, that we would not take advantage of the country’s healthcare or education systems, and that we would not remain in the country beyond our allotted time. We used our phones to wrangle up bank statements and e-mails about grants and lines of income, and he then had us go to the waiting area to sit with 15 other folks awaiting their fates. After 20 or so minutes of awkwardly sitting and wondering what heinous crimes the other inhabitants of this customs purgatory had committed, Tara and I were called back to the counter. Apparently he had been convinced that we were not national security threats, and would, in fact return to the US to pursue our respective careers. He let us know that if we were not out of the country by June 15th, he would be sending agents after us. I wanted to ask if they would be on horseback, but decided that humor, or humour, was not a language he was fluent in. And thus is was that more than an hour and a half after we arrived at the border, we were allowed to proceed. Following that somewhat harsh and prolonged (un)welcome, we got in the car a bit frazzled, a bit irate at being made to feel like criminals, but more than ready to do some birding. We made a beeline for a great birding spot I had visited during my last trip to BC; the George C. Reifel Bird Sanctuary. It was a short 30 min drive from the border, and upon arriving, we gulped down our lunches, paid our entrance fees, and walked in to the sanctuary. The first thing one notices upon entering the sanctuary is the noise. Wheezings, whistles, honks, and squawks seem to emanate from every patch of water, bush and walkway. And the source of all that sound is ducks. Hundreds of waddling, nipping, flapping, pooping and vocalizing ducks. The three most common species near the entrance were mallards, American wigeon, and wood ducks. The mallards were most abundant and vocal, the males sporting striking iridescent green heads, bright orange bills and feet, and black curly-cue tails. The wigeon were next most common, and were smaller and less aggressive than the mallards. Females and males both share rich pinkish-brown plumage on their backs and flanks, and the males have an emerald green ear/cheek patch, and a cream-colored swath on their foreheads, earning them the nickname “baldpate” from hunters. Wood ducks were the least common of the three but easily most conspicuous, with the males radiating a kaleidoscope of colors. One was perched on a fence post, contrasting wildly with the grays and browns of the winter-world around him.  An immature Bald Eagle flies towards a flock of Snow Geese, which take to the skies. George C. Reifel Bird Sanctuary, British Columbia. An immature Bald Eagle flies towards a flock of Snow Geese, which take to the skies. George C. Reifel Bird Sanctuary, British Columbia. We continued past the duck mob scene, on the look-out for a pair of northern saw-whet owls we knew to be in the area. We located them both, thanks to the small gathering of photographers at each. The owls were maybe 100 meters away from each other, and both were within a few meters of the trail. They appeared nonplussed by the attention they garnered, and remained tucked in to their respective vegetation; one hidden away in a holly bush, and the other among drooping boughs of a Douglas Fir. These diminutive owls are not much larger than a robin, their bright yellow eyes set in an overly large head, with tawny backs, and white and brown streaks on their breasts. Whenever I see an owl, I can’t help but lament all the unseen owls I must walk past on a regular basis. Seeing these two owls so close to a heavily traveled trail only made that sensation stronger. We left the owls to the other photographers, and followed the path to the outer loop trail where we could see out over an expanse of marsh stretching to the Strait of Georgia. Hundreds of snow geese and dozens of trumpeter swans gathered at the edge of the marsh to feed on the grasses. These birds had flown down from their breeding grounds in Alaska and the Arctic to winter in the temperate climes of coastal BC. But their presence had also attracted the attention of predators, and dozens of bald eagles patrolled the area. Every so often, an eagle would fly in the direction of the geese, igniting a firestorm of white and black as the geese rushed into the air. We never saw a serious hunt, but we did watch the eagles joust for prime perches, and on one occasion, two immature birds grappled in mid-air, locking talons for a few moments as they spiraled downward before they released and parted (see below). Rough-legged hawks and northern harriers also navigated the airspace over the marshes, dropping to the ground when detecting a possible prey item. While attempting to capture one of the harriers on film, I struck up conversation with another photographer, and she told me about a nearby spot (Brunswick Point) that was supposed to be great for short-eared owls. I am always on the hunt for good opportunities to photograph short-ears, so when I caught up to Tara, I told her about the owl spot, and she agreed that we should investigate it when we wrapped up at Reifel. We slowly birded our way back to the entrance, and headed towards the point. We pulled in to an area that we thought was the parking lot for the point, and began walking the dike trail that headed north. A mile and a half later, we arrived at the actual parking lot for Brunswick Point, and after kicking ourselves over the lost time, we followed the path in. Almost immediately we saw our first owl, flying low over a field with its distinctive bouncing flight. Short-eared owls are generally crepuscular, meaning that they are most active around dawn and dusk. In the short days of the northern winter, however, their periods of activity bleed into the morning and afternoon hours. Our first owl was soon joined by a second bird, and at one point there were three owls and three northern harriers cruising the area. I had my camera up constantly, trying to capture the birds as they hunted. Harriers and short-ears both use acoustic cues as well as visual ones to locate prey, and when a sound of interest (the rustle of some grass, the squeak of a vole) hits their parabola-like facial disks, they wheel around to investigate. This behavior makes them great fun to watch, but a real bear to photograph. Two owls began hunting the same patch of marsh, and with hisses and soft screams, they met in midair, grabbing at each other with their feet. Like the eagles earlier, they locked talons briefly, tussling over access to that patch of marsh, and then separated, one victorious, and the other forced to vacate the vicinity.

A large Cooper’s hawk appeared in a naked tree at the edge of the marsh, and one of the owls took notice. It looped over to the tree and passed close by the perched hawk, perhaps sending a message to the hawk that it had ventured into owl territory and should be careful, or maybe telling the hawk that the owl was a formidable predator too, and was not on the menu. Whatever the message, the hawk seemed completely disinterested, barely glancing at the owl, and instead kept its eyes locked on some shrubs a little distance away. The hawk launched itself from the tree, dropping quickly towards the ground and then flying right over the marsh grasses towards the thicket it had been watching. It disappeared into the vegetation, and did not reemerge, at least not while I watched. The hour was getting late at this point, and we had a long trek back to our car, and a 30 minute drive to the ferry terminal. We reluctantly turned around and headed back to our car. As the day faded into gray, we drove to the Tsawwassen terminal, boarded the huge ferry to Duke Point on Vancouver Island, and crossed the Strait of Georgia in darkness. When we arrived on Vancouver Island, the cars in our bay were given the OK to head out, and the vehicles on either side of us began moving forward. We, however, could go nowhere, because the truck in front of us remained driverless. What was happening? Was this some sting operation our border patrol agent had ordered? I sat in growing disbelief that we had somehow parked behind the one person who had not returned to their vehicle and could be god-knows-where. The guy behind me yelled for me to go around, but I was right up on the truck’s bumper as we had been instructed, and could go neither forward nor backward. As the drivers behind us got more agitated and began clamoring for the boat workers to do something, a startled head appeared in the truck in front of us; the driver had clearly fallen asleep and missed all the commotion of off-loading. He quickly turned the engine over, put it into drive, and the line of cars was allowed to exit the boat. We looped through the car ramps and joined the mass exodus, like a herd of cattle being driven towards new foraging grounds. We drove into the thickening fog, and when the terminal road hit the highway (BC 1), we headed south towards Ladysmith. 25 minutes of fog-obscured driving later, we turned off the 1 onto Chemainus Road, continued on a few hundred meters, and were finally at our destination. We parked on the side of the road, stretched, and descended the 82 steps to our unit. It was dark, but we could hear the water lapping at the seawall a few feet away, and after locating the key, we opened the glass door, and stepped in to our new home by the sea.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

About the author:Loren grew up in the wilds of Boston, Massachusetts, and honed his natural history skills in the urban backyard. He attended Cornell University for his undergraduate degree in Natural Resources, and received his PhD in Ecology from the University of California, Santa Barbara. He has traveled extensively, and in the past few years has developed an affliction for wildlife photography. Archives:

|