|

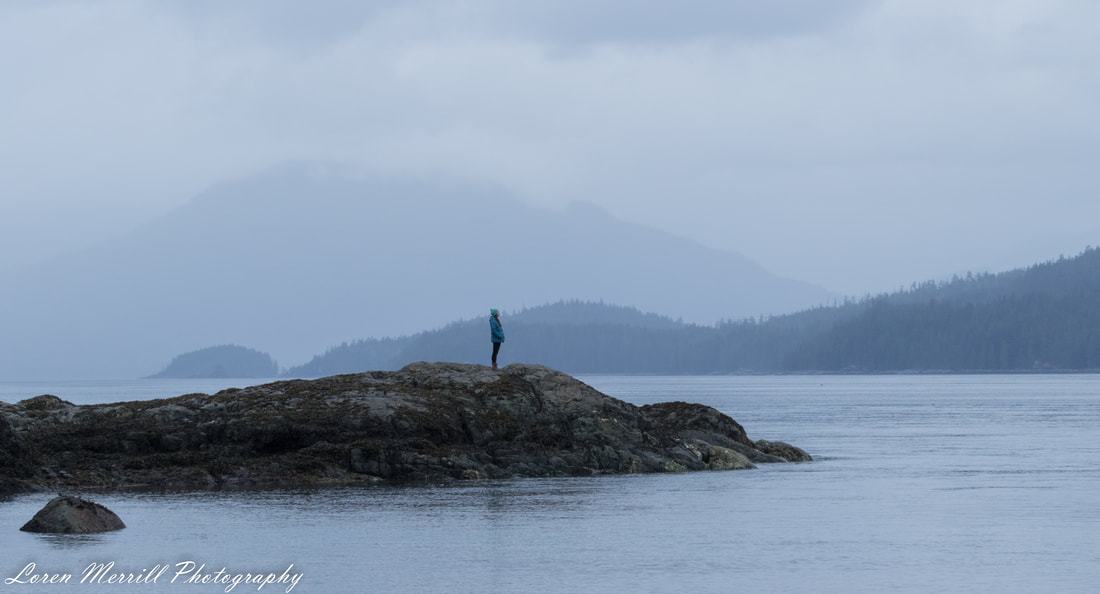

When we decided that we would be moving to the Pacific Northwest for our writing retreat/wildlife adventure, we hoped that we would have opportunities to encounter lots of marine organisms. As some of the previous posts can attest, we have had a bit of luck in this regard. But one of the prime natural attractions of the northwest is orca watching, and for the first three months of our stint in British Columbia, we had struck out on orcas. That all changed the day before we left Quadra Island. As a result of serendipitous events, and a wonderfully generous friend, we found ourselves bundled up in bright red survival suits, skimming over the waves in a large zodiac boat. We navigated our way among some of the Discovery Islands in search of a pod of orcas that had been sighted earlier. After an hour or so, we came around a rocky headland, turned to head up into a large cove called Teakerne Arm, and saw the first dorsal fins piercing the water. A pod of orcas consisting of maybe 8-10 individuals was swimming around, exhibiting a sort of fission-fusion dynamic; whales would come together into one large group, and then they would split off into groups of 3 or 4. The pod was composed of a few young whales, not much bigger than a dolphin in size, a few intermediate-sized whales, and two or three large adults, one of whom had a massive dorsal fin that curled over at the tip. The whales were quite active, and seemed to be exhibiting hunting behavior, although it was unclear what they were consuming. There are two genetically and behaviorally distinct groups of orcas in the nearshore waters of the Pacific Northwest—“resident” orcas which eat only fish, and “transients” which eat other mammals, including seal, sea lions, dolphins, porpoises, sea otters, and even baleen whales. One of the other guide boats thought it was a transient pod, but we never saw any sign of other marine mammals, and in a few of my photos, it looks like the whales have fish in their mouths, although it’s hard to make out. At any rate, we reveled in watching the whales slap their tail flukes against the water, “spy-hop” (where they go straight up out of the water part ways to get a look around), lunge, and breach. The young whales were involved in all these activities, learning the ins and outs of being a proper orca. After a few hours of sharing the water with these apex predators (which have never been known to mistakenly or purposefully attack a human in the wild) we turned around and headed back towards Quadra. Along the way we stopped to watch a group of bald eagles, a lone raven, and a turkey vulture squabble over access to a recently deceased Steller sea lion that had washed up on a remote rocky ledge. Following that engaging but slightly morbid stop, we swung by an isolated rock island that was populated with sub-dominant male Steller and California sea lions. This gathering of bachelors appeared to be putting on a clinic for how to look lazy. One big male half-heartedly scratched his back, another lay on its side with a flipper raised as if in greeting, and the others were in various states of repose. The young California bulls looked especially goofy with golden tufts of fur sprouting from the top of their heads. We didn’t remain long at Bachelor’s Island (coming soon to a TV network near you!) because we could see that inclement weather was headed our way. We raced to get back before the ocean and clouds joined to envelop us in a cold, wet embrace. The first drops of rain pelted us as we rounded the southern end of Quadra, but we managed to sneak into the harbor just before the rain began to fall with serious intent. We extricated ourselves from the survival suits, said goodbye, and headed back to our Quadra home for one last night. When you live somewhere for more than a month, you can really begin to put roots into the ground there. Both at Ladysmith and Quadra we found that we had developed deep connections with the local environs, including our living spaces. We also found that in adherence with some universal law of entropy, we had filled all the open spaces in the house with ourselves and our stuff. The process of compressing that back into a car-shaped space requires great inputs of energy and patience, and is accompanied by not a small bit of melancholy. But we knew great adventures awaited us, so we bid farewell to our Fox Meadows home and Quadra Island, and hopped the ferry back to Vancouver Island. Our first destination was only a short drive up the coast to a small logging community called Sayward. We stayed at a former lodge tucked into the woods for two nights before heading “up island” to Port Mcneil. The highlight of our time in Sayward was hiking an old trail to Port h’Kusam, which was a long-abandoned collection of buildings clustered in a small protected cove. Nature had reclaimed most of the old settlement, and we poked around a little before settling onto a rock point to look out into the ocean channel. The fog and clouds enveloped most of the surrounding word, and Hardwicke Island (which lay across Johnstone Strait) danced in and out of the fog. We spent an enjoyable three days in Port McNeil, and were given a wonderful parting gift in the form of a mother black bear and her two miniature bear cubs foraging on a trail just outside of town. Mom was munching away on some fresh green grass (one of their primary sources of food when they first emerge from their winter dens), and the cubs were exploring their new world, although not too far from mom. We had stopped once we saw them, but even though we were over 100 meters away, mom must have caught our scent or heard us, and she soon herded her cubs off the trail and into the forest. Elated at our first bear sightings for the trip, we hopped into the car and proceed the 30 minutes to Port Hardy, where we collected provisions for our time in Bella Coola. With an even more fully laden car, we drove to the ferry terminal, and after an extended wait, loaded ourselves and our car onto the massive ferry, and began our 19 hr journey towards Bella Coola, and our new home in Stuie (Stuix).

0 Comments

“View vignettes” are a collection of short stories centered around images I’ve taken over time. This short-story format is a recurring theme in which I’ll cover my outdoor observations more broadly, although in less detail than normal posts. We left our home on Quadra Island a few days ago, and are currently making our way north towards Bella Coola. We had an amazing final day on Quadra in which we spent the afternoon with a pod of hunting Orcas, but I’ll return to that in the next post. Today I’ll add a few short stories in the View Vignettes style, and once we’re settled in to our new home I’ll be able to return to longer posts. Return of the Rufous A few weeks back, I noticed a distinct humming sound emanating from some wild currant bushes. I had just emerged from one of the trails close to our place on Quadra, and the bushes bordered a nearby house which was outfitted with a hummingbird feeder. I looked around the bushes (but not too closely—nobody likes it when a stranger with a big camera is peering towards your windows…) and saw a flash of orange and rufous—a male rufous hummingbird. These birds winter in the southern parts of the US and throughout much of Mexico, and then in early spring, they migrate north along the west coast to their breeding grounds in the Pacific Northwest. When they head south again, they typically follow a much more easterly route through the Rocky Mountains, resulting in a large oval-shaped migration. As I mentioned in a previous post, it is thought that one of the major food sources that they use when they first arrive to their northern breeding grounds is sap, which they steal from the red-breasted sapsuckers (who, of course, are stealing it from the trees). But they will happily take over ownership of any hummingbird feeders, and then work tirelessly to chase away other hummingbirds (and bees or wasps). They are one of the feistiest hummingbird species, which is saying a lot! In the time since my initial spotting, I’ve seen or heard rufous hummingbirds almost every day. Their wings make a more metallic hum than the Anna’s hummingbird, so the two species can be distinguished by their wing tones (I’m really trying hard not to make a cheesy pun about cell phone “wing tones” here). Like the Anna’s, the rufous males have a swooping flight display that culminates in J-shaped dive, in which they spread their tail feathers when they reach the bottom of their dive. The tail feathers make a punctuated buzzing sound as the wind passes over them. If the female is impressed, she may allow the male to mate with her, and then she’ll go off on her own to build a nest and raise the nestlings. One of my goals in the Bella Coola area is to find an active rufous hummingbird nest, although they do a pretty good job of concealing them by adding pieces of lichen and moss to make them look just like part of the branch. Future posts will tell if I get lucky. An Unexpected Marine Visitor On the day of the Pacific white-sided dolphin adventure a few weeks back, I had another unexpected mammal encounter. The dolphins had just exited Drew Harbor at Rebecca Spit in a fantastic finale, and I was slowly making my way around the shoreline snapping photos of a group of surf scoters foraging in the now-calm waters. I noticed what looked to be a large nose swimming towards the shoreline about 100m away, and looked through my binoculars to see what it was. At first I thought it was a river otter cruising the harbor, but as the dark body got closer I realized it was an American beaver. Beavers are the largest North American rodent, and are one of the few animals that engineer the surrounding environment to suit their needs. They do this by building dams across streams and small rivers, which then flood the upstream area. Beavers are common now across most of North America, although they were extirpated from many areas during the 1600-1800s due to intensive trapping for their valuable fur. In spite of their current abundance, they are rarely seen except at dawn and dusk. On top of that, they typically reside in freshwater bodies. They clearly navigate across salt water when dispersing to or from islands, but the only other time I found evidence of beaver activity around salt water was 25 years ago, and it was one beaver-felled tree in a small cove in Maine. Having one emerge from the ocean in the late afternoon was therefore quite a surprise. I squatted down low and waited to see what the beaver would do. Beavers have pretty poor eyesight, but excellent hearing and smell, and I hoped that the slight wind wouldn’t carry my scent to the beaver. The beaver emerged from the water and took a few tentative steps onto the muddy shore. It then reared up on its haunches and sniffed at the air. It turned its head from one side to the other sniffing, and then took a few more steps onto shore and repeated the maneuver. It was facing the wooded edge of the beach, and after a few moments, it turned around and entered the water again. It swam a little ways towards me, slowly lumbered out of the water, and performed the sniffing routine again. I was fascinated by this unusual behavior and after considering a few options, decided that the beaver was most likely either smelling for trees or sniffing out a new home. Beavers will travel relatively long distances in search of their favorite foods (they love alders, birches, and willows) but I had no idea where this beaver had come from. There was a large estuary on the far side of the harbor but that would have been a least a mile away. If this were a beaver in search of a new territory, it could have traveled quite a distance looking for a suitable pond or stream to call home. Whatever it was sniffing for, it didn’t find it while I was watching. I slowly exited the area in the hopes of not disturbing the beaver, and left it to its mystery mission. Next Week: Orcas!

“View vignettes” are a collection of short stories centered around images I’ve taken over time. This short-story format is a recurring theme in which I’ll cover my outdoor observations more broadly, although in less detail than normal posts. The Curious Weasel: One of the fiercest, but possibly cutest predators on Quadra Island is the American mink. These small weasels are semi-aquatic and can be found around both fresh and salt water. Here on Quadra all of my mink encounters have been along the coastline, where the mink was either running the logs on the beach, traversing rocky ledges, or darting in and out of rocky piles (kind of reminiscent of the “whack-a-mole” game). Mink are lean little carnivores and can fit into tiny holes (they are limited by the size of their head) in their pursuit of small mammals, crabs, insects, birds, snakes, frogs, etc. And when mink are startled by something (like a giant with a camera) they usually retreat into the nearest crevice. But their curiosity almost always gets the better of them. Last week, my wife and I were hiking with my parents when we encountered a particularly inquisitive mink. We had stopped for lunch at a narrow causeway linking Quadra and Maude Islands, and I was exploring the nearby area. I caught sight of a little brown blur zipping around a rock pile and ran around to the other side of it in an attempt to position myself somewhere I would get the mink coming towards me. My plan worked—a little too well--and the mink caught sight of me and vanished into the rocks and logs. But this mink couldn’t resist coming out for a closer look, and within seconds it was inching its way out from under a log, straining to get its sights on me. This game continued: me creeping to see the mink, and the mink creeping to see me. At one point I was sitting on the edge of a rock jumble, waiting for the mink to emerge where I had last seen it (perhaps 4-5 meters away). Instead of popping up there, the mink had crept even closer (about 2 meters) and was just sitting there, peering up at me. I didn’t want to startle the animal by moving my camera, and it just so happened that the camera was pointed in the direction where the mink had newly appeared. So I clicked off a few shots (in silent mode), hoping I had gotten lucky. I hadn’t. Unless you like images of mink feet, in which case we should talk. Common Loon Showdown: Loons are currently dotting the coastal waters around the island, and many have molted into their breeding plumage. While weeks ago they donned muted black and white, they now sport jet black feathers with white speckles accents. One evening last week I went for a quick walk at Rebecca Spit when I came across a pair of common loons foraging near each other not far from shore. There were a handful of other bird species present, and my attention was split among them and the loons. The two loons would occasionally swim past each other, turning their heads when they did so in order to keep an eye on each other. I thought this was some form of pair-bonding behavior, and when the two birds dove at the same time, I turned to watch a group of harlequin ducks engaging in their usual shenanigans. Suddenly, there was a large splash. My attention quickly turned to the loons as they burst from the water, and faced off in a ritualized showdown. Elevated partially out of the water, the loons stretched their wings wide, arched their necks forward, and called at each other. They maintained these elaborate postures as they floated closer to one another until they were beak to beak. Then right before the point of touching, one bird seemed to deflate, and sank back down onto the surface of the water. With the matter of social dominance settled, the two birds drifted apart to forage on their own. The Insatiable River Otter: Almost every river otter I’ve seen has either been looking for something to eat, in the process of eating, of cleaning up after eating. So when I noticed an otter along the shoreline last weekend, I was not surprised to find that it was eating something. Curious to learn what this particular otter was eating, I crept down to the water’s edge and slowly made my way closer to it. The otter was fully engaged in munching down its meal, which appeared to be some kind of fish. I snapped a bunch of photos, took some video, and watched the otter enjoy its meal. When it had finished eating, the otter turned, splashed through the waves, and began swimming away. A small group of harlequin ducks watched nervously from the shore as the otter swam nearby. When the otter dove underwater, the ducks decided they didn’t want to take any chances and flew off. With the otter and ducks gone I, too, decided to leave the scene. But once I began walking down the beach, the otter decided to reappear. The otter had surfaced and was swimming towards me with something large and silver in its mouth. I sat down on the wet beach rocks to see what would unfold. As the otter emerged from the waves, the fish in its mouth came free and began splashing through the shallows. The otter quickly regained control of its prey and with both paws it grabbed the fish (which turned out to be a large flounder) like a kid with a giant piece of pizza. The otter ravenously consumed the entire fish then turned and porpoised through the water a few times before diving. Feeling certain the otter was sated, I got up and again began walking away. When I had walked maybe 50 meters I looked back to see the otter returning to shore with yet another flounder in its mouth. I continued walking on, marveling at the otter’s ability to put away a significant portion of its body weight in seafood in the matter of 30-45 minutes. The Amazing Newt Ball: The island’s rough-skinned newts are still on the move in their quest for love, and most of our driving trips include a pit stop to remove newts from the road. In a previous post I discussed the matting aggregations known as “newt balls”, in which males wrestle over access to a female. A few days ago, I was exploring a logging road near our house when I came across a small drainage ditch located just off the road. I looked into the clear water and quickly saw a handful of newts positioned around the basin. A sudden movement caught my attention and I realized that there was a cluster of newts tucked in among a few rocks – a newt ball! It was difficult to determine how many newts were there at first, but soon the cluster began turning and writhing, and the competition for access to the female in the middle began to heat up. As the newt ball turned, a few of the males on the periphery fell away, and then it was down to two males. The victor quickly maneuvered the female away from the other male and a few late-comers, and then swam her off to a quiet area where he would deposit a spermatophore (sperm packet) in the hopes that the female would pick it up with her cloaca. The little pool had newt eggs attached to pieces of submerged vegetation, which were a testament to previous successful newt ball wrestling matches. The Sluggish Snake:

The onset of spring has triggered the emergence of a number of animals, including the island’s garter snakes, of which there are two or three species. Garter snakes spend the winter in underground hibernacula and appear when the weather begins to warm. Of course, warm spring days can be followed by cold spring days, and that has been the case for the past few weeks. My wife and I were hiking on the Nugedzi Lake trail about a week and a half ago on one of these cold spring days when we came across a common garter snake lying on the trail. The snake didn’t seem interested in or capable of moving; most snakes will quickly slither away when approached, but this one just laid there, motionless. I used this rare opportunity to take a couple of shots. When I was done I went to move the snake off the trail and just as my hand got close to the snake, its forked tongue came out. Snakes “taste” the world around them with their tongues, and this snake was trying to figure out what sort of a threat I might be. Of course, if I’d been a real threat, the snake would have been in trouble a long time before the tongue came out. Very slowly, the tongue curved upwards and then downwards before being retracted. At that point, the molecules that had bound to the tongue were transferred to an olfactory organ in the roof of the mouth called the Jacobson’s (or vomeronasal) organ, which then allowed the snake to process and decipher the different chemical scents. This tongue action is usually a rapid phenomenon, and I suspect the slow-motion version of the behavior was due to the day’s low temperatures and lack of sunlight. Another possible explanation for the snake’s sluggish behavior is that it could have recently consumed a newt. Common garter snakes are one of the few animals that can eat newts without dying—garter snake populations that overlap with the newts appear to have evolved a degree of tolerance to the extremely potent tetrodotoxin found in the newts. Apparently these snakes aren’t completely immune to the poison, however—people have reported that snakes will become temporarily immobilized after eating a newt. I think we see a similar phenomenon in humans after the Thanksgiving dinner. Although, to make it truly comparable, the turkey would have to be would be laced with cyanide... After taking a few more photos, I gently escorted the cold/stoned snake off the trail and we continued on with our hike. We are currently living in a land of islands. Or perhaps it should be a sea of islands? Whatever it is, islands dominate our local geography. Of course the defining feature of islands is that they are surrounded by water, and are thus both buffered by, and buffeted by, the forces of the ocean. The warmer winters and cooler summers that temperate islands are renowned for are a product of something called the “maritime effect.” The basic principle of this thermal moderation is that oceans take longer to warm (and cool) compared to the land, and the local climate of areas bordering oceans is similarly tempered. In stark contrast to this moderating effect is the fact that islands can also be subjected to the unfiltered power of an angry ocean. Oceanic storms are capable of unleashing massive amounts of energy onto unprotected islands in the form of waves, wind, and precipitation. In the Pacific Northwest, these factors work in concert to create some of the richest and most productive terrestrial and marine environments on the planet. As a result of this productivity, the waters around Quadra Island are home to a rich diversity of marine mammals; 16 species of cetaceans (whales and dolphins), two sea lions, harbor seals, and if you consider the river otters and coastal wolves that navigate these waters, that’s 21 species (although many of the cetaceans are extremely rare in these waters). I’ll be focusing on four of the marine mammals we’ve encountered in our time here, beginning with the harbor seal. Harbor seals are common in the temperate waters along both coasts of North America, and can be seen hauled out on rocks or swimming close to shore. They are on the small side (for marine mammals) with adults generally reaching 4-6ft in length, although they can top 300 lbs in weight. They are not particularly adept at moving around on land (unlike sea lions, harbor seals cannot use their front limbs for support), but if you’ve ever wondered what a giant sausage bouncing across a beach looks like, these animals do a good impression. Once in the water, however, harbor seals have the grace of a bird in flight. One brisk morning a few weeks back I was fortunate to watch one gliding effortlessly through the water below me as I sat perched on a rock ledge. The seal swam by a few times about 3 meters (~10 ft) below the surface, peering up through the crystal-clear water at me in an attempt to determine if I was a threat or not. I sat motionless on the lichen-covered rock, looking down at the mottled gray and black torpedo as it traveled through its marine world. Sea-stars, urchins, mussels, and neon-green anemones decorated the underwater rock face, but the seal’s attention was fixed on me. Around Quadra, the harbor seals are both curious and wary of humans, and many of our encounters with them include an emphatic warning splash, in which the seal smacks the water to alert other seals in the area that a possible threat is nearby. Their cautious attitude towards humans is well-warranted; seals (and sea lions) are occasionally shot by fisher-people, crabbers, and aquaculture farmers because of undeserved anger over competition and perceived thievery. In spite of this, the local harbor seals seem to be doing well. On Quadra, they are a ubiquitous component of the nearshore waters, and we see one every time we are on the coast. Usually that entails looking out from the shore and seeing their shiny round heads bobbing in the waves as they look around and catch their breath. Near Francisco Point at the southeastern end of the island, we occasionally see them hauled out on exposed rocks at low tide, or lazing about in the calm waters. I’ve seen more than 10 individuals congregating there at once but whether that’s because the point provides good foraging, represents a good meeting place, or is a good lookout for orcas is unclear. It’s entirely possible the point provides all three of these things, which is why it always has multiple seals present. Francisco Point is also a good spot to see the other local pinnipeds—the California and Steller sea lions. A few days ago we wandered down to the point as part of our evening walk, and were treated to a mini marine mammal bonanza (meaning a small sampling of species; not a sampling of tiny species). A large group of harbor seals was cruising close to shore, occasionally engaging in some water-slapping fun, and a river otter was sliding through the water as well, spooking the harlequin ducks and scoters whenever it got too close. The ocean that evening was unusually calm, almost glassy, and we could see and hear the action in and on the water for miles around. We scanned the horizon looking for signs of whales when a splashing commotion erupted more than a hundred meters off the point. We turned towards the splashing and could see the hind flippers of some sea lions disappearing below the water. Almost immediately, dozens of birds began converging on the scene—glaucous-winged and mew gulls, double-crested and pelagic cormorants, red-breasted mergansers, common and Pacific loons, and even a pair of bald eagles. As we scanned the section of sea where the sea lions had been, the water exploded again as a large bull Steller sea lion surfaced and thrashed something back and forth before slipping back underwater. The smaller, darker brown bodies of California sea lions were also visible in the water, but we had no idea what was going on in the water. I looked at some of my photos and Tara’s video and realized that the big bull was thrashing a large fish around (probably a salmon), and that all the birds (and likely the other sea lions) were scrambling to get pieces of the fish that had been flung about. Steller sea lion males can exceed 3 meters (10 ft) in length and weigh over a ton, so a fish that looks large in their mouth is a substantial bit of seafood. The thrashing continued for a few minutes, and gradually the activity in that area died down. The birds left to pursue other food leads, and the sea lions that had congregated around the big bull dispersed. We followed suit and left the point to pursue our own food leads at home. Other than this experience, most of our sea lion encounters consist of watching lone individuals swim by offshore, snorting as they surface and forcefully exhale air through their nose. A few weeks back, however, we did get to witness some of the playful behavior that they are well-known for when we watched a few California sea lions shooting the rapids on the west side of the island. Tara and I had hiked out to Maude Island which is connected to Quadra via a narrow causeway, and from an elevated viewpoint, we could look out across Discovery Passage and over to Vancouver Island. The distance separating the two islands is a relatively narrow span at that point, but it is home to myriad navigational hazards. In fact this stretch of water (called Seymour Narrows) has some of the fastest tidal currents in the world, racing at speeds up to 16 knots. Prior to 1958, there was also a monster of an underwater rock formation called Ripple Rock that was responsible for sinking over 100 vessels. The government blew the top off the rock in 1958 in what is one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in human history to make the passage safer for ships. While it is indeed much safer to navigate now, the narrows are still treacherous for boaters due to the currents and whirlpools. But to a sea lion, those currents present an opportunity for a free water-slide run. From our lookout on Maude Island, Tara and I watched as a few sea lions below us swam slowly against the current. They took advantage of the dead water and eddies close to shore that were created by a small rocky point that protruded from the island into the current. Once they reached that point, they would push out into the current and shoot down the rapids, disappearing underwater. Five or 10 minutes later they would reappear close to shore and do the whole thing over again. The real masters of aquatic play, however, are the dophins, and I’ll wrap up this week’s post with what is probably the highlight of our time on Quadra so far. Two Sundays ago I was driving past Drew Harbor and the entrance to Rebecca Spit after a morning of hiking near Morte Lake, when I noticed a small group of people clustered on the side of the road. I glanced into the harbor to see if there was something in the water drawing the attention of the people and saw activity in the water. I pulled over, grabbed my camera and hurried to the water’s edge. Perhaps 100 meters (~330 ft) from the barnacle studded rocks I was standing on was a pod of 50-75 Pacific white-sided dolphins slowly swimming about in the shallow waters of Drew Harbor. The dolphins would swim in one direction for a while, frequently surfacing with a loud exhalation as they expelled air and water vapor from their blow-hole. Some individuals would change direction, and it would appear as though the pod was swimming in a circle for a little while. This behavior is called “milling” and after watching them mill-about for 30 minutes or so I raced home to get Tara. When we returned, the dolphins were still there, but now they had added another component to their slow meanderings; the sprint. This seemed to happen about every 30-45 minutes during which a signal would go out through the pod and they would all start racing through the water. During these sprints, the dolphins would break the surface with most of their body, but they generally wouldn’t jump out of the water. Sometimes the dolphins would sprint one way for a hundred meters, and then turn and sprint back to where they had been. The sprint would typically go on for a minute or two, after which the dolphins would return to their milling behavior. We watched this amazing show from the shore but sometimes the dolphins would get to within 15-20 meters (45-65ft) of where we stood. Tara ventured home after a few hours but I stayed behind to see if the source of this activity would be revealed. I really wasn’t sure what the dolphins were up to-were they herding schools of fish in the shallows? Were they avoiding a pod of orcas that was on the other side of Rebecca Spit? Neither scenario seemed likely. If they were fishing, where were the gulls, cormorants and other birds that almost always join in the hunt? If they were avoiding orcas why were they making a splashing commotion that would be audible for quite a distance underwater? An hour or two after Tara left, a man and woman who lived on the edge of the harbor came down to chat. They told me that this was only the second time in the 27 years they had lived there that they had seen the dolphins exhibit this behavior. We chatted for a little while longer and then they continued on down the shore a little ways. I continued to take photos of the dolphins when they came close mixing in close-up shots with landscape shots in an attempt to capture the amazing backdrop against which this show was occurring. Suddenly, there was a solitary splash. Then another. In the midst of the milling, a few individuals had begun full body breaches, jumping clear of the water and smacking back down on their sides, backs or bellies. This was clearly a signal, and it spread through the pod immediately. The dolphins exploded into motion as they began the final act to their day-long spectacle. All traveling in the same direction, the dolphins tore through the water, leaping and breaching as they went. They raced around the perimeter of the harbor, passing within 20-30 meters of where I kneeled at the water’s edge, and within a few minutes they had exited the harbor. I stood up and laughed with joy and shock at what I had just witnessed. I had been hoping for an acrobatic display, and I got that and then some. But what had that entire day of activity actually been? Was it related to breeding displays? Was this group-bonding? Was it a day-long choreography session that closed with the actual show? I don’t know—any of those options seem plausible. All I know is that I was lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time to bear witness to an amazing natural event.

Next week’s post: TDB. |

About the author:Loren grew up in the wilds of Boston, Massachusetts, and honed his natural history skills in the urban backyard. He attended Cornell University for his undergraduate degree in Natural Resources, and received his PhD in Ecology from the University of California, Santa Barbara. He has traveled extensively, and in the past few years has developed an affliction for wildlife photography. Archives:

|