|

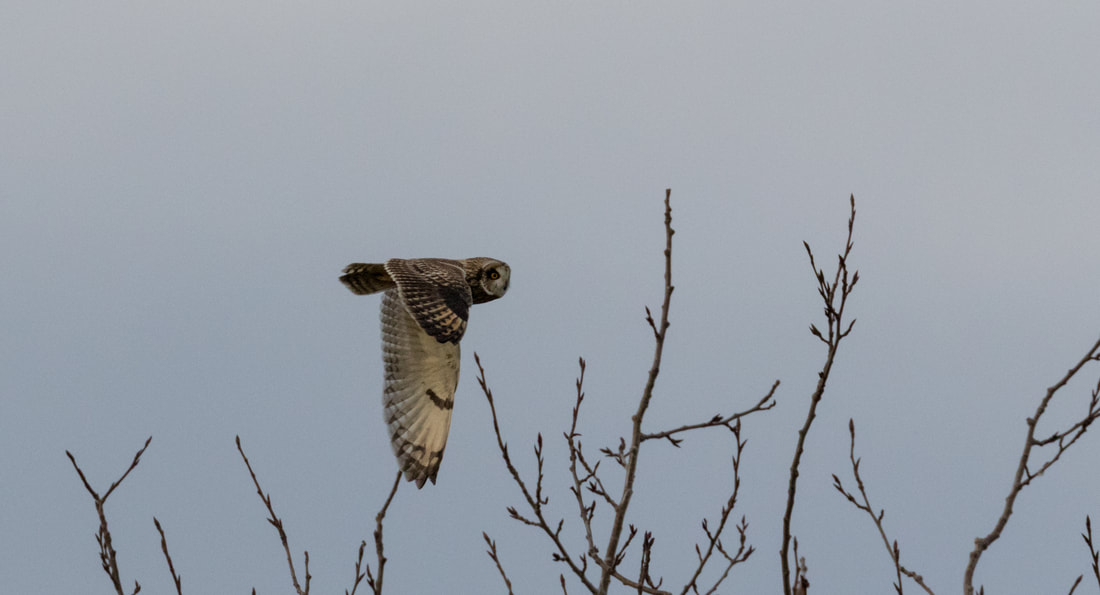

I woke well before dawn, my brain coming online in a flash of realization that today would be our final day of travel. Tara and I had a quick breakfast with our wonderful hosts, Fred and Fran, grabbed some extra coffee for the road, and were on our way. We made a quick stop at Trader Joe’s for some supplies (e.g. copious amounts of cheese for Tara) and then continued north towards what we thought would be smooth sailings across the border. We were mistaken. As we approached the border crossing, there were two booths open; one had a slightly shorter line, so naturally I opted for that one. In what must be a universal law of waiting or traffic lines, the one I selected immediately stopped moving. Three cars passed through the other gate before our first car was allowed to proceed. I probably should have realized then that things were not going to unfold the way I had envisioned. When we finally made it to the booth, the agent at the gate was quite friendly, and chatted with us about a rescue bulldog we should keep an eye out for when we got to Ladysmith, and the best cinnamon rolls in town (Old Town Bakery). Almost as an afterthought, he mentioned that we would need to go inside to talk with one of the customs agents because of the proposed length of our stay (5-6 months). We pulled over, and went inside, where we were subsequently interrogated for 30+ minutes by a dour young customs agent sporting an unusual hairdo; that is, he had very little, and what he had was gelled into little spiky islands. I’m not sure if there was a deeper meaning in his hair with respect to the current global trend towards greater insularization, but it was clear from the outset that he took his job very seriously. It also became clear that he considered two biologists with Ph.D.s looking to spend 5 months in his country writing papers and grants, highly suspicious. He wanted us to convince him that we would not seek illegal employment, that we would not take advantage of the country’s healthcare or education systems, and that we would not remain in the country beyond our allotted time. We used our phones to wrangle up bank statements and e-mails about grants and lines of income, and he then had us go to the waiting area to sit with 15 other folks awaiting their fates. After 20 or so minutes of awkwardly sitting and wondering what heinous crimes the other inhabitants of this customs purgatory had committed, Tara and I were called back to the counter. Apparently he had been convinced that we were not national security threats, and would, in fact return to the US to pursue our respective careers. He let us know that if we were not out of the country by June 15th, he would be sending agents after us. I wanted to ask if they would be on horseback, but decided that humor, or humour, was not a language he was fluent in. And thus is was that more than an hour and a half after we arrived at the border, we were allowed to proceed. Following that somewhat harsh and prolonged (un)welcome, we got in the car a bit frazzled, a bit irate at being made to feel like criminals, but more than ready to do some birding. We made a beeline for a great birding spot I had visited during my last trip to BC; the George C. Reifel Bird Sanctuary. It was a short 30 min drive from the border, and upon arriving, we gulped down our lunches, paid our entrance fees, and walked in to the sanctuary. The first thing one notices upon entering the sanctuary is the noise. Wheezings, whistles, honks, and squawks seem to emanate from every patch of water, bush and walkway. And the source of all that sound is ducks. Hundreds of waddling, nipping, flapping, pooping and vocalizing ducks. The three most common species near the entrance were mallards, American wigeon, and wood ducks. The mallards were most abundant and vocal, the males sporting striking iridescent green heads, bright orange bills and feet, and black curly-cue tails. The wigeon were next most common, and were smaller and less aggressive than the mallards. Females and males both share rich pinkish-brown plumage on their backs and flanks, and the males have an emerald green ear/cheek patch, and a cream-colored swath on their foreheads, earning them the nickname “baldpate” from hunters. Wood ducks were the least common of the three but easily most conspicuous, with the males radiating a kaleidoscope of colors. One was perched on a fence post, contrasting wildly with the grays and browns of the winter-world around him.  An immature Bald Eagle flies towards a flock of Snow Geese, which take to the skies. George C. Reifel Bird Sanctuary, British Columbia. An immature Bald Eagle flies towards a flock of Snow Geese, which take to the skies. George C. Reifel Bird Sanctuary, British Columbia. We continued past the duck mob scene, on the look-out for a pair of northern saw-whet owls we knew to be in the area. We located them both, thanks to the small gathering of photographers at each. The owls were maybe 100 meters away from each other, and both were within a few meters of the trail. They appeared nonplussed by the attention they garnered, and remained tucked in to their respective vegetation; one hidden away in a holly bush, and the other among drooping boughs of a Douglas Fir. These diminutive owls are not much larger than a robin, their bright yellow eyes set in an overly large head, with tawny backs, and white and brown streaks on their breasts. Whenever I see an owl, I can’t help but lament all the unseen owls I must walk past on a regular basis. Seeing these two owls so close to a heavily traveled trail only made that sensation stronger. We left the owls to the other photographers, and followed the path to the outer loop trail where we could see out over an expanse of marsh stretching to the Strait of Georgia. Hundreds of snow geese and dozens of trumpeter swans gathered at the edge of the marsh to feed on the grasses. These birds had flown down from their breeding grounds in Alaska and the Arctic to winter in the temperate climes of coastal BC. But their presence had also attracted the attention of predators, and dozens of bald eagles patrolled the area. Every so often, an eagle would fly in the direction of the geese, igniting a firestorm of white and black as the geese rushed into the air. We never saw a serious hunt, but we did watch the eagles joust for prime perches, and on one occasion, two immature birds grappled in mid-air, locking talons for a few moments as they spiraled downward before they released and parted (see below). Rough-legged hawks and northern harriers also navigated the airspace over the marshes, dropping to the ground when detecting a possible prey item. While attempting to capture one of the harriers on film, I struck up conversation with another photographer, and she told me about a nearby spot (Brunswick Point) that was supposed to be great for short-eared owls. I am always on the hunt for good opportunities to photograph short-ears, so when I caught up to Tara, I told her about the owl spot, and she agreed that we should investigate it when we wrapped up at Reifel. We slowly birded our way back to the entrance, and headed towards the point. We pulled in to an area that we thought was the parking lot for the point, and began walking the dike trail that headed north. A mile and a half later, we arrived at the actual parking lot for Brunswick Point, and after kicking ourselves over the lost time, we followed the path in. Almost immediately we saw our first owl, flying low over a field with its distinctive bouncing flight. Short-eared owls are generally crepuscular, meaning that they are most active around dawn and dusk. In the short days of the northern winter, however, their periods of activity bleed into the morning and afternoon hours. Our first owl was soon joined by a second bird, and at one point there were three owls and three northern harriers cruising the area. I had my camera up constantly, trying to capture the birds as they hunted. Harriers and short-ears both use acoustic cues as well as visual ones to locate prey, and when a sound of interest (the rustle of some grass, the squeak of a vole) hits their parabola-like facial disks, they wheel around to investigate. This behavior makes them great fun to watch, but a real bear to photograph. Two owls began hunting the same patch of marsh, and with hisses and soft screams, they met in midair, grabbing at each other with their feet. Like the eagles earlier, they locked talons briefly, tussling over access to that patch of marsh, and then separated, one victorious, and the other forced to vacate the vicinity.

A large Cooper’s hawk appeared in a naked tree at the edge of the marsh, and one of the owls took notice. It looped over to the tree and passed close by the perched hawk, perhaps sending a message to the hawk that it had ventured into owl territory and should be careful, or maybe telling the hawk that the owl was a formidable predator too, and was not on the menu. Whatever the message, the hawk seemed completely disinterested, barely glancing at the owl, and instead kept its eyes locked on some shrubs a little distance away. The hawk launched itself from the tree, dropping quickly towards the ground and then flying right over the marsh grasses towards the thicket it had been watching. It disappeared into the vegetation, and did not reemerge, at least not while I watched. The hour was getting late at this point, and we had a long trek back to our car, and a 30 minute drive to the ferry terminal. We reluctantly turned around and headed back to our car. As the day faded into gray, we drove to the Tsawwassen terminal, boarded the huge ferry to Duke Point on Vancouver Island, and crossed the Strait of Georgia in darkness. When we arrived on Vancouver Island, the cars in our bay were given the OK to head out, and the vehicles on either side of us began moving forward. We, however, could go nowhere, because the truck in front of us remained driverless. What was happening? Was this some sting operation our border patrol agent had ordered? I sat in growing disbelief that we had somehow parked behind the one person who had not returned to their vehicle and could be god-knows-where. The guy behind me yelled for me to go around, but I was right up on the truck’s bumper as we had been instructed, and could go neither forward nor backward. As the drivers behind us got more agitated and began clamoring for the boat workers to do something, a startled head appeared in the truck in front of us; the driver had clearly fallen asleep and missed all the commotion of off-loading. He quickly turned the engine over, put it into drive, and the line of cars was allowed to exit the boat. We looped through the car ramps and joined the mass exodus, like a herd of cattle being driven towards new foraging grounds. We drove into the thickening fog, and when the terminal road hit the highway (BC 1), we headed south towards Ladysmith. 25 minutes of fog-obscured driving later, we turned off the 1 onto Chemainus Road, continued on a few hundred meters, and were finally at our destination. We parked on the side of the road, stretched, and descended the 82 steps to our unit. It was dark, but we could hear the water lapping at the seawall a few feet away, and after locating the key, we opened the glass door, and stepped in to our new home by the sea.

0 Comments

Our second night on the road was spent in Gillette, Wyoming: “the perfect stopover on I-90” according to one of their marketing campaigns. We pulled in a little after dark, and as we approached the front entrance to our hotel, we were mildly surprised to see that it was actually attached to another hotel sporting a giant waterslide snaking out the front of the building. The slide was fully enclosed, so no risk of hypothermia for the brave watersport enthusiasts, but it all seemed just a bit out of place. At least it did to me; Tara was bemoaning the fact that her bathing suit was somewhere at the bottom of the car. We walked past the giant plastic chute, checked in to our room, and then headed to the local convenience store (AKA Walmart) for some dinner supplies. We grabbed a nice-looking prepared salad and some microwavable dinners, and after self-checking out, we grabbed our few food items and headed towards the door with our dinner in our arms. As we neared the exit, the greeter called us over, saying (in somewhat less friendly tones than she had used when welcoming us a few minutes prior)- “No bags?” “No, we don’t need any for just a few items,” we responded. “Come on guys, I’m going to need to look at your receipt. When you don’t have bags, it just looks suspicious.” Tara was miffed, and wanted the woman to understand that we were simply trying to cut down on plastic consumption (especially having just purchased microwaveable meals...), but I was just tired, and had no appetite for educating the purported greeter/shoplift-foiler about the broader implications of plastic bag use at that moment. We left the woman, and the gaping cultural divide, behind us and returned to our hotel room to enjoy our unpackaged meal in comfort. The next morning, we were again up before light, this time on the road towards Missoula, Montana. The day passed easily, accented by occasional groups of pronghorns dotting the hills alongside the highway. These animals (formerly known as pronghorn antelope because of their resemblance to Old World antelopes) are the second fastest land animals on the planet, capable of running 55 mph for extended periods of time. There are no predators that come close to that velocity in North America, so why bother having all that extra speed? The answer is thought to lie in the past; pronghorns shared the American prairies with a suite of now extinct predators, including what’s been called the American cheetah (closely related to the mountain lion, but supposedly capable of cheetah-like speeds), and a hyena, which may have been a long-distance runner like some of its African relatives. So the pronghorn’s speed and endurance are possible holdovers from an age when it had a very different predator guild to contend with. Some call this phenomenon “the ghost of selection past” (which is really an adaptation of Connell’s “ghost of competition past” idea). The closer we got to Missoula, the more majestic the scenery became. We pulled in to our friend Maria’s driveway around dusk, and spent the evening at a trendy local restaurant. The next morning we joined our host for her morning walk with Ollie, her amiable four-legged housemate, and I rapidly lost sensation in my extremities as the heat was drawn from my hands and feet by the 13 degree Fahrenheit temps. But we did hear a (fool)hearty American dipper singing from the partly frozen river coursing through the small park, and that made up for any pain in my body. We returned to the house, grabbed a quick bite at a local coffee shop, and were on the road again. That day was our last big leg; 8 hours of drive time with an evening destination of Vashon Island in Puget Sound, where we would spend the night with my cousins Gabe and Christina, and their three kids. We hit a few pockets of low clouds/fog along the way, and joined what felt like a luge run shooting down the western side of the Cascades with all our fellow motorists seemingly abandoning their brake pedals. We made excellent time and caught the sunset ferry across to Vashon. As the boat pulled away from the dock, we were afforded stunning views of Mt. Rainier, complete with alpenglow on its snow-covered slopes (see image above). Not a bad welcome from the Pacific Northwest.  The setting sun from an overlook at Washington Park, Fidalgo Island, Washington. The setting sun from an overlook at Washington Park, Fidalgo Island, Washington. We arrived on Vashon Island after the 10 min ferry ride, and drove a short distance to my cousins’ house nestled in the deepening shadows of the cedars and hemlocks. Tara and I thrilled at the lush surroundings, the hunter greens of the conifers, mosses and ferns. Not for the first time, we contemplated asking Gabe and Christina if they would perhaps consider adopting us. We went inside the house, with its beautiful post and beam design and open layout, and were welcomed in with a feast. Dungeness crab roll appetizers, hand-made pizzas, steamed mussels, and a fresh salad. After luxuriating around the dinner table, Gabe suggested a night hike, so we ventured off into the woods to explore by moonlight. The waxing half-moon was high in the sky, and cast so much light that we only needed to turn the flashlight on a few times to navigate tricky portions of the path. We walked to a small meadow and paused, craning our heads back to take in the moon and the constellations, all of which popped in the crisp air. I could make out details of the plants around us, the individual stems of grasses, and marveled at how much light the moon was reflecting down to us. After a few minutes of this, we turned around and made our way back to the house for the night. The following morning we lounged over breakfast and made plans for birding our way to Vancouver Island over the next two days. We hopped the late morning ferry at the north end of Vashon, and upon hitting the mainland, turned north to head up the coast. We exited the 5 for Anacortes, and pulled in to Skagit’s Own Fish Market to share an exquisite crab roll and prawn taco for lunch. Christina had recommended the crab roll the previous night, and we were not disappointed. With full bellies and thoroughly satisfied taste buds, we were ready to do some birding. We drove the short distance to Rosario Beach and got out to wander the small coastal grounds. We spied harlequin ducks, horned and western grebes, common loons, pelagic and double-crested cormorants, black oystercatchers, and a handful of other water and terrestrial birds. The park was stunning, but the experience was tempered slightly by the overbearing acoustic presence of fighter jets and P-3 Orions performing maneuvers a little distance away. We packed ourselves back into our car and headed to Washington Park, located at the eastern end of Fidalgo Island. We walked the loop road, which hugged the coast for most of its length, and stopped to watch the erratic activities of chestnut-backed chickadees and golden-crowned kinglets that decorated the vegetation like animated Christmas-tree ornaments. A bald eagle materialized through the branches, clutching an old duck or gull carcass in its talons. It landed nearby, looking around to see if any potential thieves had noticed it, but unhappy with its perch, it soon launched back into the air and disappeared around a corner. I happened upon a local bath-house of sorts; a shallow puddle in a pebbled opening where golden-crowned kinglets, chickadees, juncos and song sparrows were taking turns wading in, and vigorously shaking themselves in the clear water. Tara called me away from the bathers to see a trio of harlequin ducks foraging close to the rocks along the shoreline. I made my way down to the water’s edge and set-up with my camera to see if I could get lucky with the lighting. Just as two of the birds began exploring an area with optimal golden light, two border-patrol agents walked down and paused nearby, looking out over the water and discussing matters of national security. The ducks seemed slightly agitated (they had almost certainly made their way there from Canada, after all) and quickly moved along, although I was able to get a few shots off (image below). We continued walking and arrived at an overlook just as the sun began easing itself down into the hills to the west (image above). Once the sun disappeared, the thermostat dropped rapidly, and we quickened our pace in an attempt to outrun the cold. We got to the car with a few minutes of light to spare, and drove the 5 minutes to Christina’s parent’s house where we spent an enjoyable evening eating, drinking wine, and chatting about birds, Florida, and politics. The next day would be our last of travel; or would it? Our border-crossing experience did not go quite as planned. Next post: Crossing the border, birding the Reifel Bird Sanctuary, and arriving at our new home.  Mount Rushmore Mount Rushmore It all began with a plan. A simple plan that would take us from the agricultural desert of central Illinois to the temperate rainforests of coastal British Columbia to write, hike, and photograph for a few months of winter and spring, followed by a trip to southern Africa for our honeymoon. We would pack up our lives in Champaign, Illinois, put everything into storage that we wouldn't need for the next 8 months, and take the rest with us. Simple. It did not take long for "simple" to begin unraveling as we realized that our journey west was actually going to start with a journey east to Maine for Christmas, and then south to Florida for a conference. "The best laid plans..." huh. I would like to say something like "undaunted, we continued packing and organizing our lives" but I was beginning to feel rather daunted as our departure date approached and the spatial limitations of our storage unit and car became apparent to me, as did the realization that I may have some hoarding tendencies. Throw in Tara's PhD exit seminar and defense, multiple large grant applications, my job applications and interviews, having to clean out our home of 5 years and our offices... let's just say that the preamble to our journey took on a life of its own and gifted me more than a few white hairs around my temples as an early Christmas present. I won't belabor the details of our preparations or the trips to Maine and Florida, except to say that we managed to get some good naturing in at both places, and that in a cruel (but perhaps appropriate) twist for two people who study immunity and disease ecology, we both contracted a nasty norovirus from my nieces as a late Christmas present. Not one of the better years for unasked for gifts. But early on the morning of January 10th, we packed ourselves into our little Kia Niro, bracing against the 16 degree Fahrenheit temperature that still permeated the car, and began our trip west in earnest. We drove away from the brightening eastern horizon, passing out of the town that we had lived and worked in for 5 years although not a place that had ever really felt like home to us. The morning light caught up to us as we sped along, tallying whatever wildlife we could see along the margins of the highway. Red-tailed hawks were abundant, perched in trees and on fenceposts, and all fluffed up against the cold. We spotted a lone coyote wandering an empty ag field, and a handful of American kestrels hovering over the frosted grasses off the road. Once we passed into Iowa we began seeing bald eagles and rough-legged hawks in addition to the red-tails, and as the sun dipped below the horizon to the west and darkness overtook us, we crossed over into South Dakota and stopped for the night in Sioux Falls. The next morning we were up again before first light and on the road so that we would have some time to explore Badlands National Park. The partial US Government shutdown (ongoing and in its 32nd day as of this writing) had not closed the loop road to the Badlands, so we were still able to access the park. The impact of the shutdown quickly came into focus as the facilities were all closed (read, no bathrooms), and we came across a young man emerging from one of the trails dressed in a black leather jacket and cowboy hat, carrying a large antlered deer skull. Removal of any natural or historical objects is prohibited in national parks, but with only skeleton crews available for policing the national parks, I suspect this sort of thing has been a common occurrence nationwide. Soon after passing the young man, we came across a herd of bighorn sheep grazing not far from the road. We pulled over and I grabbed my camera to take some shots of the animals. Soon after I rolled the window down, the herd began walking towards us, and within a few minutes they were crossing the road about 5 meters in front of us. There were a few large rams with massive curled horns spiraling outwards, a few females with more sharply pointed horns that angled backwards, and a few young of the year animals with short nubbins for horns. The lead ram (pictured above) seemed interested in our car, and for a moment I had visions of him using his battering ram of a skull to send us a message, but he quickly led the herd across the road and down to a patch of coarse, yellowed grasses. We watched them feed for a while, and then continued on, snaking our way through the park which we had almost to ourselves. After another hour or so we came across a large and active town; a black-tailed prairie dog town. The town was dotted with burrow entrances, and the town's inhabitants were taking advantage of the relatively warm, snow free weather to forage on grasses and seeds. When we pulled up alongside an active area, the plump little ground squirrels would often run/waddle their way back to their burrow entrance, and then turn to look at us, with some rearing up on their hind limbs and giving chirping alarm calls (see image below). Soon they would return to their normal business of eating and socializing, however, and act as if we weren't there. We passed many active colonies as we made our way out of the park, and with a handful of hours of daylight left, we decided to pass by Mount Rushmore. We drove slowly through the Black Hills with tiny snowflakes materializing in the air. As we ascended, the scattered patches of snow that dotted the ground turned into a solid pack, blanketing the hills around us. When we were close to the park entrance, we rounded a corner and caught sight of the monument; the enormous granitic faces of Washington, Roosevelt, Jefferson and Lincoln stared out from the mountain. We continued on towards the park entrance, but unlike at Badlands, here they were collecting entrance fees even though the facilities were closed. We only planned to spend a few minutes there, so we opted to return to a roadside viewpoint, where we hopped out and clicked a few images (see inset). We returned to the road, and made our way to Gillette, Wyoming where we would spend the second night of our journey. To be continued. |

About the author:Loren grew up in the wilds of Boston, Massachusetts, and honed his natural history skills in the urban backyard. He attended Cornell University for his undergraduate degree in Natural Resources, and received his PhD in Ecology from the University of California, Santa Barbara. He has traveled extensively, and in the past few years has developed an affliction for wildlife photography. Archives:

|