|

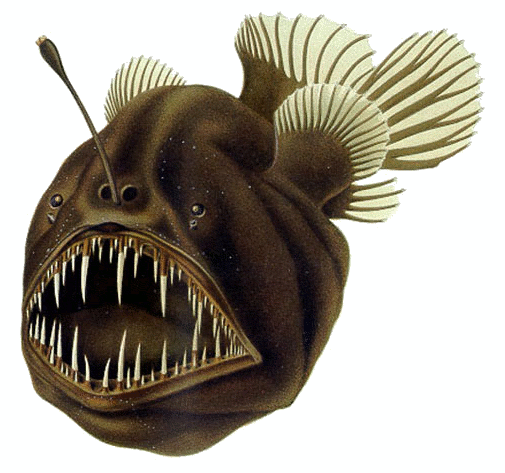

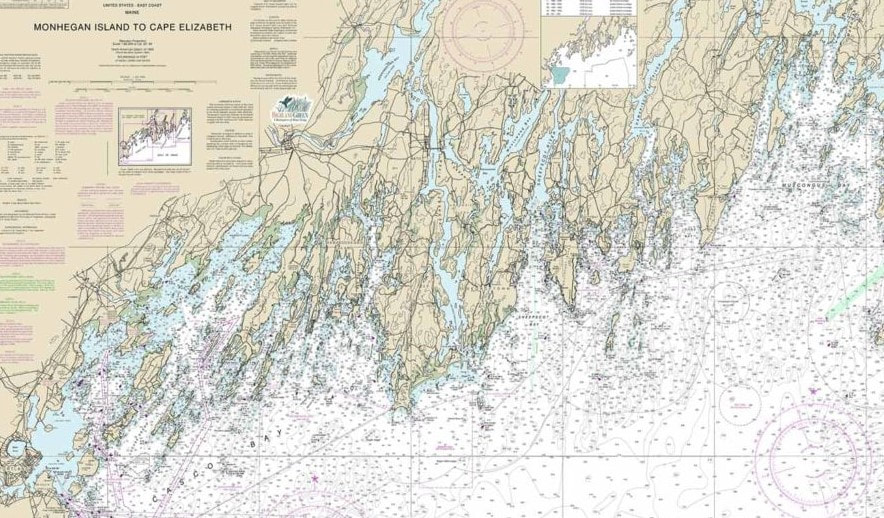

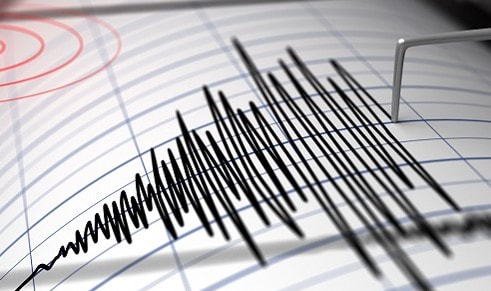

Most temperate regions of the world abide by the classical four season paradigm: Winter, Spring, Summer, Fall. Maine, with its strong independent streak has nine. Maybe more. There are, of course, the classical seasons, but Maine offers up a few more, very specific, mini-seasons. Unlike the big four, these mini-seasons don’t have calendar start and end dates. Instead, they are defined by meteorological or biological phenomena. For example, between Winter and Spring is Mud Season. Mud Season is the period during which the ground begins to melt, but before the vegetation has begun growing. The ground thaw typically starts at the surface and progresses downwards, which means that the moisture from the melting soil can get trapped between the top layer and the retreating ice. Extra-moist soil happens to be the key ingredient for mud, and voila! Mud Season. For most Mainers, Mud Season is something to be tolerated as they wait for the emergence of spring, and the return of nice weather. But there are some for whom Mud Season represents a return to simpler times. It presents an opportunity for these people to put on their galoshes and go jump in a mud puddle. Of course, for many people, galoshes have been replaced by oversized trucks, and mud puddles have been replaced by just about anything these folks can drive their oversized trucks through. A little bit later in the year lies Maine’s most sinister season: Black Fly Season. This season actually reminds me a bit of one of those deep-sea predatory fishes, the anglerfish. For those not familiar with this denizen of the dark, anglerfish have a unique anatomical feature for which they are named; they sport a modified dorsal spine that protrudes out in front of their body, and at the end of this spine sits a bioluminescent “lure” that the anglerfish dangles in front of a mouth overflowing with teeth. The luminous lure attracts other inhabitants of the deep who think they’ve found a tasty glowing meal, only to realize too late that they are that meal. Black Fly Season is just like that anglerfish. Let me explain. People in Maine endure a rather extended Winter, which is then followed by Mud Season. By the time warm weather arrives, many folks are chomping at the bit to get outside, enjoy outdoor activities, and soak up some vitamin D. So, with the flowers blooming and the trees freshly attired in the greens they just pulled out of winter storage, people head out into the woods in droves. And that’s when the anglerfish-black flies spring their trap. These tiny, blood-feeding micro-predators seem to regard insect repellent as a dinner bell, and long-sleeves/long-pants and head-nets as dining room decor. Unlike the gangly mosquito, which is all legs and proboscis, the black fly is a compact little rover. They crawl up your pant legs, down your collar, under the head-net perimeter, and anywhere else (yes, anywhere else) they can smell that sweet CO2 elixir oozing out. And the bite of a black fly is an order of magnitude worse than that of a mosquito. For one thing, rather than inserting a hypodermic needle, they lacerate your skin and lap up the pooling blood. Once the biting begins, so does the psychosis. A few Junes back, Tara and I made the questionable decision to camp at Baxter State Park, deep in Maine’s north-central woods, during one of the worst Black Fly Seasons in recent history (according to the locals). Of course, we didn’t know this when we decided to head up there, and in fact, we thought the season had already passed. We were wrong. When we arrived at the park, we were full of excitement and anticipation. There were moose to see, mountains to hike, sunsets to photograph…we were mesmerized by that big glowing lure. And then the teeth closed around us. We realized we were in trouble pretty quickly. Like within five minutes of getting out of the car. The first squadron made contact while we were setting up our tent, and for the next three days our bodies were under siege. We wore long sleeves and long pants. We donned jackets. We tucked our pants into our socks. We put on head-nets. We bathed in bug spray. None of it mattered. I would sit on the shores of Sandy Stream Pond, trying to capture images of the surrounding mountains with my camera, and the black flies would crawl down the back of my pants, or find the seams in my socks where the fabric was thinnest. We climbed Mt. Katahdin, the second highest peak in New England, hoping we would lose them during the ascent, but they followed us almost to the summit. We ate meals in our car when we were at camp, and they squirreled their way inside for a quick bite of their own. We retreated into our tent, but they were there too, waiting for us among the folds of our sleeping bags. Nowhere was safe. The bites, full of the black fly’s special cocktail of numbing agent and anticoagulant, itched incessantly, and extracted a hefty mental toll on us. But it was the fear of more bites to come that finally drove us out. If I never experience another Black Fly Season, it will be far too soon. Moving from blood-meals to Maine-meals, Maine boasts a few other, culinary-oriented, seasons that are each deserving of attention, but which I’ll mention only briefly here: Maple Syrup Season (also called Sugaring Season), Blueberry Season, and the now-defunct Shrimp Season. But the undisputed king of the seasons for most Mainers and visitors (those “from away”) is Summer. For every one of my 43 years, I’ve spent at least some portion of the summer in Maine. When I was young (in the 0-9 years range), that slice consisted of one golden week in August when we would make the four-hour drive from our house in Boston to a family enclave of sorts in McFarland’s Cove. I say that it was a four-hour drive, and technically if you think of time as a constant, linear phenomenon, it did take four hours. But to a five-year old boy who was practically apoplectic with excitement, the drive involved multiple time loops, some serious backwards time travel, and actually took two weeks. As we turned off the country highway onto McFarland’s Cove Road, however, the seeimingly interminable trip was forgotten. McFarland’s Cove is one of an almost infinite number of inlets tucked into Maine’s rocky Mid-coast region. Maine’s coast, which looks like it was drawn by a hyperactive four-year-old on a sugar high, has almost 3,500 miles of coastline crammed into 228 straight-line miles. Imagine the output from a seismograph during an earthquake, and you’ve got a good idea of what the coastline looks like. For my younger self, that one cove was the center of my universe. I would pack about a month’s worth of swimming, fishing, rock-flipping and rock-skipping, snorkeling, tide-pooling, crabbing, snake-hunting, and general exploring into that one decadent week. A typical day would begin with an individual cereal box breakfast (if I was lucky, it would be some sugary delight like Froot Loops, or Lucky Charms), and once breakfast was done, I was free to roam in my natural habitat. At that time, my family lived in an urban Boston neighborhood, and while we had a lovely big backyard, for me it felt like being a little two-legged tiger confined to a zoo exhibit. I dreamt of days spent outside in pursuit of animals, and once I was in Maine, those dreams became my reality. Some days I would spend 8 hours swimming around in the chilly Atlantic water, mask and snorkel gradually adhering to my face as I searched for marine life. And the cove was full of it; crabs and hermit crabs, skates and flounders, sea urchins and sea stars, the eel-like rock gunnel, and the always thrilling lobster. Whenever I would dive down among the large patches of brown algae, however, my heart would quicken at the thought of what might be hidden among the thick fronds: the grotesque, and sure to swallow-me-whole, goosefish. There are, of course, more dangerous animals in the ocean than goosefish, and while I don’t think they keep stats on worldwide goosefish attacks, I’m pretty positive no one has ever been eaten by one. But I can pinpoint the moment the goosefish became lodged in my psyche. I was going through a field guide to the plants and animals of the eastern US when I came across its image. The goosefish, which happens to be a type of anglerfish like our deep-sea friend described above, is a bottom-dwelling predator that looks as though it has been stepped on and then covered in bits of brown doilies to conceal the damage. But the thing that captivated and terrified me was its head, which comprises about half the fish’s body and is full of dagger-like teeth. When you consider that the goosefish can approach lengths of five feet, you begin to see why it was the risk of goosefish attack that kept me from exploring the darker recesses of the cove. There may not have been records of goosefish-related deaths at that time, but I certainly wasn’t going to become the first. Here’s a fun video of a goosefish in action so you can appreciate the fear I experienced (start at 55 seconds). Despite the constant threat to life and limb, there was no place I would rather spend time. Eventually, though, I would get hungry, tired, or numb, and would have to retreat to the land. The terrestrial environs of the cove presented their own suite of exciting animals to pursue, but there was one animal that lay on a pedestal above all others: the garter snake. I loved snakes and had an insatiable appetite for catching them. I was never satisfied by simply finding one; I had to have it in my hands. Only then, when it was slithering through my fingers, biting me with its tiny teeth, and dousing me with its rancid musk was I happy. And I wanted those around me to be happy too, so I tried sharing my snake captures with others. The notion that everyone wouldn’t want a snake in their hands, or better yet, slithering down their shirt, was outside my purview at first. I was quickly disabused of my snake-outreach ideas, however, and had to content myself with sharing my snake passion with just a few other like-minded boys in the cove.

Over time, I grew out of the need to catch and hold things that I found, but it took a while. I suspect my passion for photography is an evolution of sorts for this sort of behavior. It provides an opportunity for me to capture and hold the animal without touching it. And I don’t smell of snake stink when I’m done. Next post: Summers in Maine: Part II. Subscribe to the Newsletter! If you would like to get notifications about when new posts are up and other tidbits related to the blog, sign up for the View Out the Door twice-monthly newsletter. Just email viewoutthedoor “at” gmail “dot” com with the subject header SUBSCRIBE. And if you’d like to unsubscribe, e-mail with the subject header UNSUBSCRIBE.

2 Comments

Anne Cyr

2/19/2021 01:24:10 pm

Loren - I loved reading about your childhood in the cove. I had similar experiences at Newagen, although I was not so much in the water as on the water!

Reply

Loren Merrill

3/4/2021 09:28:09 am

Hi Anne! Thanks so much! I gradually transition to more "on the water" as I got older and began windsurfing and kayaking.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the author:Loren grew up in the wilds of Boston, Massachusetts, and honed his natural history skills in the urban backyard. He attended Cornell University for his undergraduate degree in Natural Resources, and received his PhD in Ecology from the University of California, Santa Barbara. He has traveled extensively, and in the past few years has developed an affliction for wildlife photography. Archives:

|