|

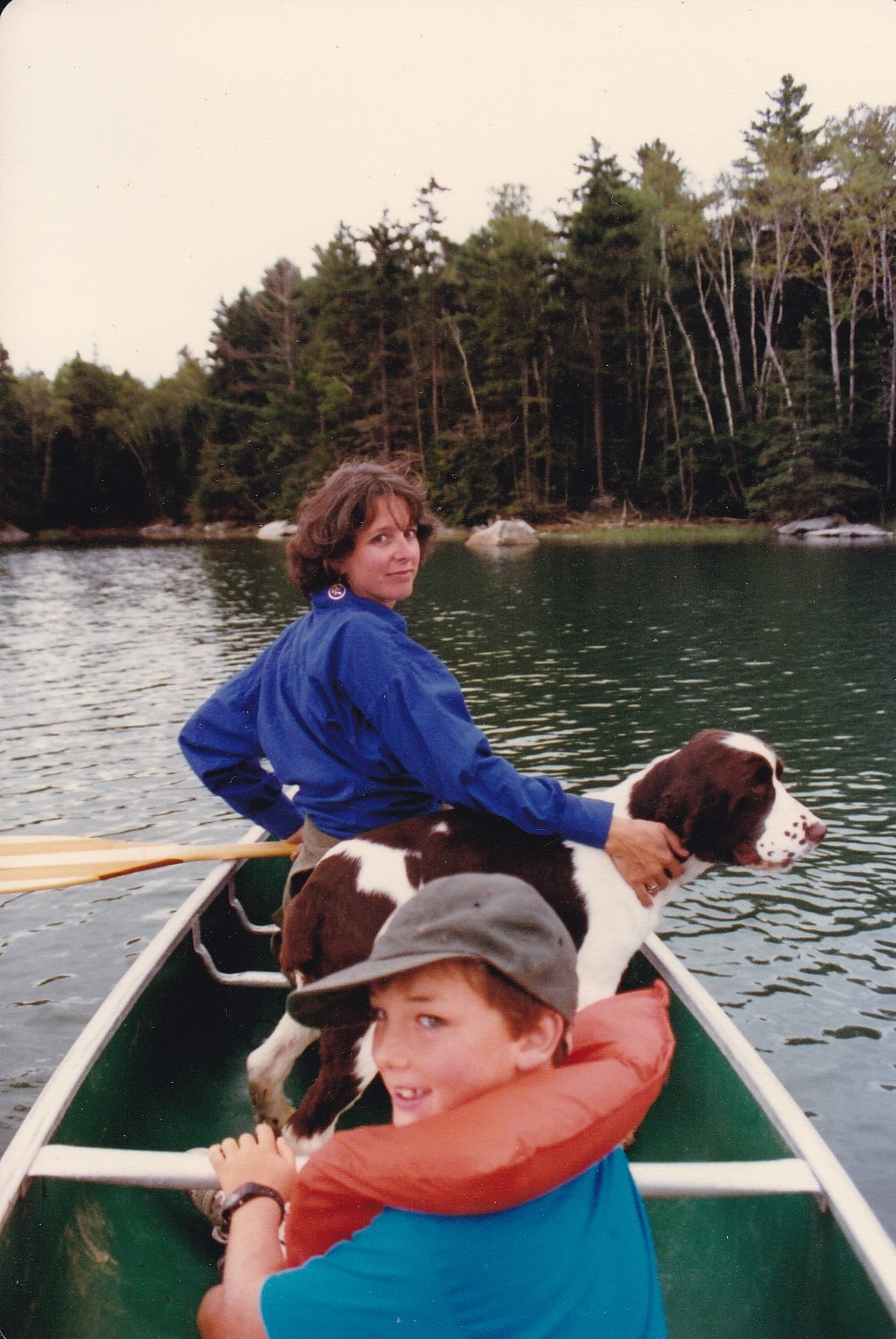

“View vignettes” are short stories centered around images I’ve taken over time. This week’s vignettes celebrate Mother’s Day with a collection of stories about the hardest workers in the animal kingdom. Mother opossum and her baby joey backpack Early last May, I was in rural Illinois conducting the spring bird count on a protected tract of forest and grassland, when some movement on the grassy road ahead of me caught my attention. I grabbed my binoculars from the car-seat and was surprised to see a very handsome opossum sauntering my way. Opossums are generally nocturnal, and most encounters happen at night (especially on the road). It was unusual to see an opossum ambling along in the daytime, but there was also something very unusual about its back—it seemed to be moving all on its own. I looked closer, and realized that its back was squirming with baby opossums. Mother opossum continued in my direction, and it wasn’t until she was 2-3 meters (6-9 feet) away that she also realized that something was amiss—a giant object (my car) was blocking her path. Virginia opossums have pretty poor vision, but they have excellent olfactory (smelling) abilities, and she was trying to make sense of the car (and me) with her nose. She took a few hesitant steps towards the car, and then decided she would detour around us. Her troop of nine babies seemed unperturbed, and took the opportunity to reposition themselves and adjust their grip on her fur. Baby opossums (like all marsupials) begin life as pink, hairless, and blind joeys no bigger than a jellybean. Once they are born, they immediately crawl to the mother’s pouch (no small feat for a jellybean) and latch onto a nipple, where they continue to develop for the next few months until they get too big for the pouch. At that point, they clamber onto the mom’s back and morph into joey backpacks. They hang out on their mom’s back for a few weeks until one day, they fall off, and begin their solitary juvenile and adult lives. The nest out our door Most people in North America have probably seen the American robin performing its maternal duties. Robins are ubiquitous throughout much of North America, from the pristine forests of the wild north, to urban backyards and suburban parks across the continent. And it is in our very own backyards – either on a low hanging branch, or below an awning of our home- that we find their nests and get a glimpse into the parent-offspring relationship of this common species. A mother robin’s parenting role begins even before she lays any eggs. The female will select an appropriate location for the nest, and then work on nest construction. This might happen quite rapidly, or may occur over the course of a week or more. The latter scenario is more common for the female’s first nest of the year, when temperatures can fluctuate dramatically. A few years ago, we had a robin pair that decided to use an outdoor shelving structure on our balcony for their nest site. This was rather exciting because it gave us a behind-the-scenes view into the robins’ private lives; we could closely watch the robins’ activities from our living room without disturbing them. Mother robin began her construction process by laying a mesh of grass and sticks, which she slowly built up into the rough edges of a nest. The eggs need a well-shaped cup for both physical safety and thermal incubation. When it came to the cup-shaping phase, this robin would add some muddy grass, and then wiggle down into the nest to create the perfect mother robin-shaped cup. As you can see in the video below, she wiggled in almost a complete 360 degree rotation so that the cup would be properly shaped in every direction. Once the nest is built, the mother robin will lay one sky-blue egg per day (usually in the morning), until her clutch is complete. Young robins, or those in poor condition usually lay fewer eggs (2-3), whereas older and healthier robins will lay more (4-6). Four is the norm, and that is just what our neighbor robin laid. After 12 days of mom incubating the eggs, they hatched, and then both mom and dad began the never-ending task of feeding the four nestlings. Once the nestlings were a few days old, we would occasionally join them on the balcony, and mother robin quickly adjusted to our presence. The dad, on the other hand, would alternate between scolding us, and ignoring us, but they both continued to provide a constant food supply for their babies. The incubation and nestling period are both critically important for proper development of young robins, and the high-level mothering our robin delivered surely provided her young with a great head-start in life. A mother-cub trip to the seashore Many of the black bears in coastal British Columbia have learned to take advantage of marine resources, and oftentimes, this extends beyond their classic fish-catching behaviors. Black bears in undisturbed areas will make their way to the shoreline at low tide and forage in the intertidal zone. There they slurp up just about any food items they can find; crabs are a delicacy, as are bivalves such as mussels and clams. In September 2017, I spent some time with a mother black bear and cub on Vancouver Island. During my time with this bear duo, I was able to watch from a kayak as mom led her growing cub around a quiet inlet. They traversed the exposed flats side by side, searching for marine morsels. The cub would parrot the behavior of the mom, crunching up chunks of barnacles, and flipping rocks to get at whatever was hiding beneath. While mom could flip over hundred pound rocks with ease, the cub would knock over smaller, more cub-appropriate ones. At one point they took a quick siesta, but like many kids at nap time, the cub was more interested in carousing, and engaging in a bit of play-fighting with mom. Black bears remain with their mothers for the first year and a half of life or longer (depending on if/when the mother gets pregnant). During this time, the mother provides her cub with food, protection (male bears are a major threat to cubs), and an education in both proper foraging techniques and threats to avoid. A few weeks ago we saw a mom and her two very young cubs in Port McNeil, BC. But we have yet to see any cubs here in the Bella Coola valley (despite our 30+ bear sightings). It could just be random chance, but I suspect that the moms are keeping their cubs out of the bear-packed valley for the time being until the cubs become a little more agile and can escape from threats. As much as we’d love to see some more mother and cub duos, a mother bear that feels her cubs are at risk will fiercely defend them from perceived threats, and that is one wild experience I’d rather forego. I’d like to wrap up with a special thank you to my own mom! In support of my passion for the animal world, she patiently tolerated the ever-changing menagerie of animals that made their way into my bedroom. This included a collection of frogs, turtles, snails, salamanders, the occasional injured bird, free-range rats (just in my room—not the whole house of course), and, despite her own very strong feelings towards them, snakes. I loved snakes as a kid, and I was constantly on the prowl for them. I loved them so much that I would occasionally put them down my shirt in a bizarre display of bravado, or as part of a summertime talent show. And there was the one time I let a garter snake share a sleeping bag with me for the night because I was afraid it was too cold outside. Through all of this, my mom encouraged these interests and helped instill a deep-seated curiosity, respect, and love for the natural world. Thanks mom, and Happy Mother’s Day to moms everywhere! Next week: Trip to the Plateau

1 Comment

Margaret

5/12/2019 06:23:53 pm

Thank you, Loren. A moving tribute to early experiences which clearly influenced your outlook on life. I am glad to have been a part of that.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the author:Loren grew up in the wilds of Boston, Massachusetts, and honed his natural history skills in the urban backyard. He attended Cornell University for his undergraduate degree in Natural Resources, and received his PhD in Ecology from the University of California, Santa Barbara. He has traveled extensively, and in the past few years has developed an affliction for wildlife photography. Archives:

|