|

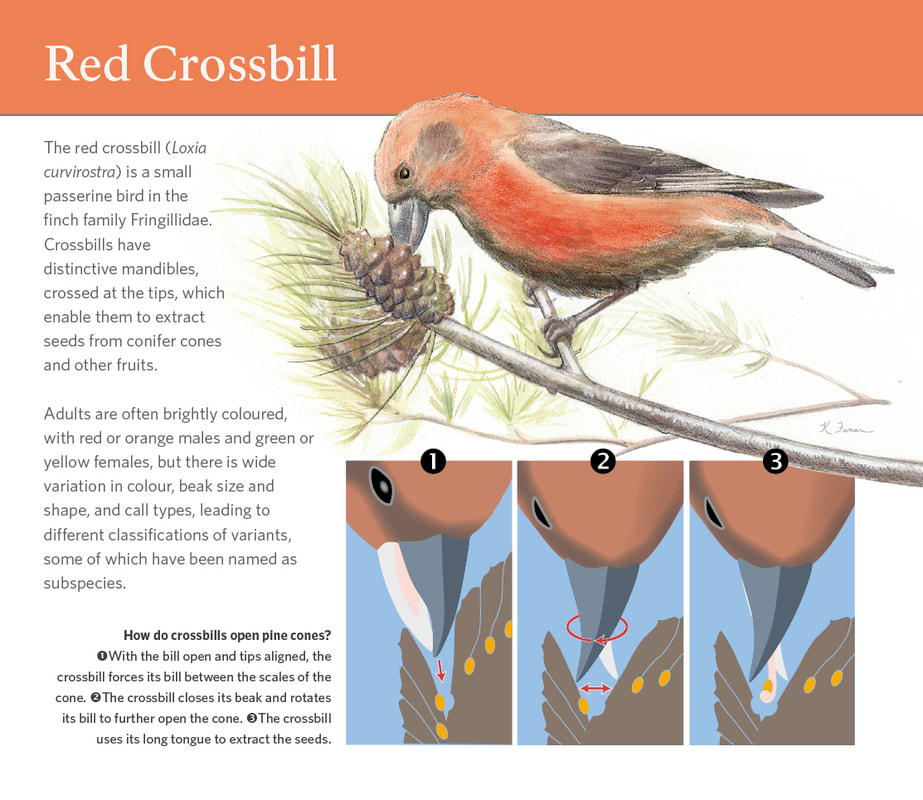

The birds of spring and summer are gone, shunning our cold, snowy landscapes for the warm, lush forests of the tropics and subtropics. They take with them their audacious colors—the tanager reds, the oriole oranges, and the warbler yellows. In their place we get a more season-appropriate grouping of birds; the winter finches. Birds that fall within this general category are northern finches of the family Fringillidae, and they often appear in human-populated portions of the continent during the winter months. One of the interesting traits of these winter finches is that many of them exhibit dramatic fluctuations from year to year in their movements. One season they can be dripping off the branches in a particular area, and then when the food runs out, the birds will vanish and might not be seen again for years. These movements coincide with the availability of their preferred food resources, which can be highly unpredictable. When food becomes scarce in their far-north home regions, these birds have no qualms about packing up and going on a road trip. These forays are called “irruptions” (not to be confused with a volcano’s “eruptions,” although it is fun to visualize an eruption of finches), which essentially means a mass invasion into a new area. Some of the winter finches are likely familiar to many folks; purple finches, evening grosbeaks, and pine siskins are common winter visitors to backyard feeders across the country, but there are a host of other species in the grouping too. White-winged and red crossbills, common and hoary redpolls, gray-crowned, brown-capped, and black rosy-finches, Cassin’s finch, and pine grosbeaks can all be considered, to varying degrees, part of the winter finch flock. In this post I’ll cover two subgroups- the crossbills and the grosbeaks- and talk a little about their ecology and some of my fondest bird watching memories. I’ll begin with the crossbills. North America is home to two* species of crossbill: white-winged crossbills and red crossbills. (*There are 10 distinct populations of Red crossbills which can be distinguished by their calls, and to some degree by morphological differences. They are currently considered one species but they appear to prefer to mate with others that share the same call type, and may eventually be split into separate species). These birds have already made a few cameos in the blog, but their unique ecology and behavior warrant some real coverage. Let’s start with the obvious—their bills are crossed. Why would a seed-eating bird have evolved a bill that looks so incredibly ungainly for eating seeds? It turns out that this is an ingenious adaptation for getting access to pine seeds in pinecones that still haven’t opened yet. In general, birds have much stronger biting muscles than mouth-opening muscles (note: this is generally true across taxa—a saltwater crocodile, for example, can crush bones with a 3,700 pounds per square inch bite, but you could probably clamp its jaws shut with just the force of your hands—assuming the croc’s head and body were immobilized and you didn’t care that much about keeping your hands). A crossbill can leverage its biting strength into extracting pine seeds in six easy steps: 1) opening its bill, 2) aligning the tips, 3) wedging the bill between cone scales, 4) closing its bill (with those strong muscles), 5) turning its bill slightly sideways, and 6) using its tongue to extract the seeds from among the opened scales. Their uniquely engineered bills allow crossbills to access a food resource unavailable to most other animals. It also makes them look rather awkward when they’re trying to collect grit from the ground. One of the unifying traits across the winter finches is their proclivity for grit—small bits of rock. Finches love grit because it helps the gizzard with the tough job of grinding up the hard seeds that they ingest. One of my first, and closest, encounters with a crossbill was at the Wonderlake Campground in Denali National Park in Alaska a few years back. My wife and I were eating some of our meager food rations at one of the picnic tables (there’s a story behind our food shortage that I’ll share in the future), when we were joined by a juvenile white-winged crossbill. It flew to the ground and began scraping the dirt off the small stones that covered the ground around the table, and then licking up the little grit pieces it had created. The bird did this within a few meters of us and seemed completely nonplussed when I got down on the ground to document some of the behavior with my camera. Since then, I’ve encountered many hundreds of crossbills, siskins, finches, and grosbeaks collecting grit from dirt roads—it’s the best time to get close to these species. As is the case for a number of the winter finches, crossbill ecology is tightly coupled with that of their conifer food sources. Pine, spruce, fir, and hemlock seed production can be wildly unpredictable, so many of the winter finches have adopted nomadic lifestyles to varying degrees. They travel across the landscape following seed production, often journeying hundreds or even thousands of miles in search of good conifer seed crops. But the crossbills have taken their association with food to another level. If a group of crossbills finds a good seed crop, they will build nests, lay eggs, and raise nestlings. And they can do that in the middle of winter in frigid places like the mountains of Idaho, Wyoming, Alberta, British Columbia, and Alaska. This mind-boggling feat is possible only because parent crossbills can feed their nestlings seeds. Most songbird nestlings need an arthropod-heavy diet to survive and grow, but many members of the finch family get a seed-heavy diet as chicks. The ability to provision their nestlings year-round, coupled with the unpredictable nature of their food source, has led crossbills to this highly flexible breeding strategy. Our next group of winter finches is the grosbeaks; the evening and pine grosbeaks. These stocky finches of the north are a real treat for the majority of bird-watching people in North America because their ranges, for the most part, are restricted to northern and high elevation regions of Canada and the US (and Mexico for the evening grosbeak). Both species undergo irruptions, although the evening grosbeak’s irruptions can occur throughout most of the contiguous US, whereas the pine grosbeak’s irruptions are limited to parts of Canada and the northern portions of the US. The grosbeaks have a more varied diet than that of the crossbills, incorporating insects, spruce buds, berries and fruits, and the seeds of many tree species. As their name suggests, grosbeaks have quite substantial beaks, and generally know how to use them. Despite eating a variety of soft foods, their bills are designed for cracking open tough seeds. Evening grosbeaks, for example, typically remove the flesh of berries and small fruits, and eat the seed inside after cracking it open with their bills. I haven’t experienced the bite of either pine or evening grosbeak, but my fingers have been savaged by northern cardinals and black-headed grosbeaks (both close relatives) as part of my research, and I feel fortunate to have retained all of my digits in the aftermath of these encounters. One of my earliest bird watching memories (aside from the “penguin” I saw in a pond in Maine when I was 8…) was of a pine grosbeak in New Hampshire. I was 10 and in the midst of a two-week overnight summer camp adventure at Camp Wildwood. It was my first sleep-away summer camp experience, and after the initial trepidation had worn off, I found that I quite enjoyed sleep-away camp, especially one geared towards outdoor pursuits like hiking, canoeing, swimming, and the like. All these years later, most of the memories have blurred together in a haze of communal meals, bedtime jokes in the cabin, running through the woods, and splashing around in the lake. But there a few memories that stand out against the fog of time, and one is of a solitary female pine grosbeak foraging on the ground about 10 feet away from me while I was drying off after a swim. At the time I knew nothing of their ecology, or even that it was an interesting sighting (a nearby counselor told me what the bird was), so I’m not sure why that memory is so vivid. For whatever reason the scene has become canalized in my mind, and I can still clearly recall watching the plump gray bird with a yellow head pecking at small seeds on the ground. The next time I saw a pine grosbeak was about 15 years later when a flock of them descended on a crabapple tree in my parent’s yard in Maine right around Christmas. They spent a glorious snowy afternoon hopping from branch to branch, gobbling down the old, wrinkled fruits. And then they were gone, and it was probably another 15+ years until I saw my next one. Now, when I hike in the mountains just above our place here in Colorado, I find myself in the pleasing situation of being awash in pine grosbeaks. Evening grosbeaks also hold a special place in my bird watching heart. As a junior in high school, I spent the spring semester at the Chewonki Foundation’s Maine Coast Semester program in the Midcoast region of Maine. This was a hugely formative experience for me, and solidified my resolve to become a biologist. Part of the science curriculum was bird identification, including identifying birds by their songs and calls. As an avid birder, I knew almost all of the bird vocalizations already, except for the calls of the evening grosbeak. This was a bird I had yet to encounter, but one which I was especially excited to see. Their striking plumage and massive bill, coupled with the mystique of their nomadic ways had made them an irresistible attraction for me. I memorized the calls, and late one winter afternoon I was walking through the woods when I heard the calls overhead. I looked up to see two birds fly past at about twice the tree-top height, uttering the guttural “flight calls” I had heard through the speakers of a tape deck or the headphones of my Walkman so many times. They were gone in seconds, and even though I had failed to see any of the birds’ distinctive features, I was thrilled by my encounter with these birds of the north. Their calls are now indelibly imprinted on my brain, and no matter how many years pass between encounters, I instantly recognize their vocalizations when I hear them. Living at 9000 feet elevation in the Colorado Rockies, I’m right in the heart of the winter finch kingdom and get to see some of these birds on a daily basis. But as the winter season unofficially gets underway this week (we’re experiencing our 8th snowfall of the season right now), these birds could be on the move. And while winter finch movements are hard to predict, every year Ron Pittaway makes a general forecast based on observations of the finches’ food resources up north. This year doesn’t look to be a good one for irruptions, but these birds are always a possibility to show up in unexpected places. So as you carve up your turkey or tofurkey this coming Thursday, keep one eye on the bird inside, and one eye on the birds outside.

Happy Thanksgiving to everyone in the US! Next post: TBD Subscribe to the Newsletter: If you would like to get notifications about when new posts are up and other tidbits related to the blog, sign up for the View Out the Door weekly newsletter. Just email viewoutthedoor “at” gmail “dot” com with the subject header SUBSCRIBE.

2 Comments

I peered out through the curtain of falling snowflakes, breath condensing on the fabric of my facemask, and eyelashes sticking to one another in the single-digit temperatures. I plodded through the calf-deep snow, making my way up a narrow trail bordered by young aspen trunks and a mixture of Engelman and blue spruce, ponderosa and limber pines. I had already been out for almost two hours and aside from a few dark-eyed juncos, a flock of red crossbills, and four suspicious mule deer, the other animals appeared to have made the wise choice of hunkering down. With a high of 7 degrees Fahrenheit that day, and the mercury dropping, I was second-guessing my decision to venture out in such conditions. It was so cold I had taken the battery out of my camera and had it inside my glove along with an activated Hothands packet. I tried not to think about the cold, but instead focused on keeping my eyes and ears alert for any signs of life in the white world around me. The reasons I had forsaken the comfort of our toasty house were twofold: one, there were unlikely to be any other people out and about in such conditions, which improved my chances of spotting human-shy wildlife; and two, there was a chance the storm could bring in some interesting bird rarity. As the trail approached a dirt road, the vegetation opened up into a small meadow with a few willow and alder thickets clustered around the edges. I glanced up and saw a plump bird with a long tail atop a tall pine, swaying in the wind. My first thought was northern pygmy owl, which I had been hoping to see for weeks. I quickly realized it was not an owl at all, but another predatory bird—a northern shrike. Shrikes have an unusual ecology; they are songbirds like thrushes, sparrows, and warblers, but unlike most other songbirds, the 33 species in the shrike family are carnivorous. Shrikes eat a lot of insects, but they also eat vertebrates such as small mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians. Shrikes have a wicked hooked beak that they use to immobilize and kill their prey, and then use to tear off bite-sized pieces. These are not your run-of-the-mill backyard songbirds—just imagine watching a robin stalking mice instead of worms, and then piercing the mouse’s neck with its beak. You’d never look at robins the same way again. But shrike ecology gets even more fascinating. These fearsome predators are not armed with the same suite of tools as their contemporaries, the hawks, eagles, falcons, and owls; shrikes lack talons. Instead of talons, they have normal songbird perching feet which are not well-equipped for predatory duties. One way in which shrikes have gotten around this oversight by natural selection is to use their environment, and they have done so with gruesome efficiency. Shrikes often skewer their prey on sharp objects such as thorns, broken branches, and barbed wire. This stabilizes the prey allowing the bird to tear into the food with its beak. It is this behavior that has earned shrikes the name “butcherbirds” (their family name Laniidae is derived from the Latin word for butcher). Shrikes also store food in this fashion, and a few years ago I got to experience a shrike cache in person. I was visiting friends in Arkansas who work with another North American shrike species, the loggerhead shrike, and one afternoon we went to the territory of a nesting pair of these birds. Loggerhead and northern shrikes superficially resemble northern mockingbirds-they are about the same size and shape, and the bold gray and white plumage is relatively similar. Shrikes and mockingbirds also like to perch on exposed branches or power lines, but the shrike’s resemblance to the fruit and insect-eating mockingbirds ends there. All around the shrike nesting area there were little bodies impaled on thorns and barbed wire; frogs, snakes, lizards, grasshoppers, partial remains of small mammals, all serving as a grisly warning to any small animal in the area to watch the skies. This caching behavior allows the shrikes to store food for times when prey is less plentiful, and provides a nice back-up when the nestlings turn into adolescents and begin demanding lots of food. Back in the high elevation deep freeze of Colorado, I watched the northern shrike surveying its surroundings from the top of the pine. Suddenly it dropped through the falling snow and landed in one of the alder thickets up the trail from me. I lost sight of the bird for a few minutes, and when I had drawn even with the shrike, I could see that it was eating something. I snapped a few photos which revealed that the shrike had caught a small songbird, likely a junco or chickadee, and was hastily gulping it down, feet and all. I was impressed; this was a first-year bird (apparent from its duller mask and browner plumage), and clearly it had already mastered the art of catching avian prey. Northern shrikes eat mostly birds and small mammals in the winter months, and have been known to capture and kill prey substantially larger than themselves, including rock pigeons, mourning doves, American robins, blue jays, and lemmings. They use both sit-and-wait and active pursuit strategies for hunting and are capable of chasing down other birds in flight. It is also possible that a bit of deception is included in their repertoire. They don’t really resemble traditional avian predators like falcons and hawks, and other birds may not be alert to the danger they represent, especially if they’ve never encountered a shrike before. This was certainly not the case a few weeks past when I came across a Clarke’s nutcracker harassing another young northern shrike. The nutcracker had chased the shrike into a tall aspen and was scolding the young predator from a nearby branch, and occasionally pecking at it with its long beak. The shrike was clearly agitated, and was yelling back at the nutcracker, snapping its bill in agitation. The young shrike finally shed its agitator and flew off to pursue hunting in a more private location. The nutcracker, for its part, winged over to some nearby limber pines, likely feeling a bit of self-satisfaction at having driven off the butcher of the north. At least for the moment. Our other focal bird this week is the dipper, and like the shrikes, it is a songbird with an unusual ecology; the American dipper is North America’s only aquatic songbird. These rotund birds (also known as “ouzels”) spend their entire lives in and around water, mostly fast-flowing streams and rivers of high-elevation habitats. They are occasionally found along the edges of ponds, lakes, and marine environments, but the quintessential dipper territory is a boulder-strewn stream tumbling down the side of a forested mountain. Here these slate-gray birds can be found bobbing their bodies (hence the name “dipper”) while standing on rocks protruding from the water, or wading through the swift-flowing current, grasping the slick substrate with long, strong claws. And then, suddenly, the bird will be gone, vanished beneath the boiling surface, to reappear nearby a few moments later with a small aquatic invertebrate in its beak. A little over a week ago, I was following the South Platte River through Waterton Canyon, south of Denver, and I came across an actively bobbing American dipper. Dippers forage almost exclusively underwater and employ a variety of techniques to secure their food. The individual I found was especially accommodating and allowed me to watch it from close quarters, where I could observe many of its foraging tactics. The simplest maneuver is when it would stick just its head underwater and look around for aquatic inverts attached to nearby substrate. It also frequently plunged into the water and swam to the bottom, where it would then walk around, turning over rocks, leaves and sticks for hidden prey. This sounds straightforward, but it was able to perform this act in the very fast-flowing current by using its strong feet to hold onto the bottom. In addition to walking on the stream floor, it would occasionally swim around underwater, searching the perimeter of submerged rocks, peering into crevices and poking into cracks for attached inverts. Dippers can also pursue mobile prey underwater, chasing after minnows with powerful wing-propelled thrusts. Like other aquatic birds, dippers have a transparent third eyelid called a nictitating membrane that allows them to see clearly underwater. They also come equipped with an exceptionally warm, feather-lined wetsuit that keeps them dry and warm, even in freezing temperatures, although they have to spend a substantial portion of their day preening to keep their feather-suit functioning properly. Dippers also have low metabolic rates and higher oxygen carrying capacity of their blood relative to similarly sized songbirds, both of which are thought to be adaptations to their cold, aquatic lifestyles. Those who have seen an American dipper will probably agree that, aside from its tendency to dive under water, the most conspicuous aspect of its behavior is the constant bobbing. The function of the dipper’s dipping isn’t clear but could serve as a form of visual communication to other dippers in the area, or could help mask the dipper’s presence from predators. American dippers also have bold white, feathered eyelids, which really become apparent when the bird blinks. Like the dipping behavior, the purpose of this bold marking is unclear, but it likely serves as some signal to other dippers. On the vocal communication front, dippers produce a loud, musical song, consisting of sweet bell-like tones and harsher staccato notes. John Muir described it this way: "[H]is music is that of the streams refined and spiritualized. The deep booming notes of the falls are in it, the trills of the rapids, the gurgling of margin eddies, the low whispering of level reaches, and the sweet tinkle of separate drops oozing from the ends of mosses and falling into tranquil ponds." —John Muir, 1894. Dippers sing year-round, but they ramp up the singing activity prior to and during the breeding period in late winter/early spring. Once dippers have found a mate, they begin building their nests. Dippers build a large, ball-like nest constructed of moss on the outside, and leaves and grass on the inside. They often place their nest behind a waterfall or under a hanging structure along the side of the stream or river. Once the young hatch, the parents work full-time to keep those hungry mouths fed. These duties continue even after the chicks leave the nest, as the parents continue to provision the fledglings until they are ready to take the plunge and embrace a world no other North American songbird knows; the world under the water’s surface.

Next post: TBD Subscribe to the Newsletter: If you would like to get notifications about when new posts are up and other tidbits related to the blog, sign up for the View Out the Door weekly newsletter. Just email viewoutthedoor “at” gmail “dot” com with the subject header SUBSCRIBE. |

About the author:Loren grew up in the wilds of Boston, Massachusetts, and honed his natural history skills in the urban backyard. He attended Cornell University for his undergraduate degree in Natural Resources, and received his PhD in Ecology from the University of California, Santa Barbara. He has traveled extensively, and in the past few years has developed an affliction for wildlife photography. Archives:

|